Can you preserve a 30-year-old roll of color film and shoot it like the day it was purchased? Today I’m going to answer that question as well as give an in-depth history of one of Kodak’s most pivotal films, Ektar 25. I think that some of its history as well the results may surprise you.

Announced in October 1988 at Photokina, along with 17 other color films, Kodak Ektar 25 was introduced with its highly sensitive companion, Ektar 1000.

According to Popular Photography, it was nearly grainless and knocked the eyes out of even the most hardened film testers. Compared to Kodachrome and Ektachrome, Ektar 25 was a high contrast highly saturated C-41 film with not a lot of give. For that reason, the box was labeled, “For SLR Cameras” insinuating you should not put this in a point-and-shoot camera.

Popular Photography elaborated on what makes this a special film in their December 1988 issue.

“Ektar 25 is a slower, simplified, slimmed down version of current Kodacolor Gold 100 print film. By combining the overcoat and UV filter into a single layer, and using a single blue-sensitive emulsion instead of the two conventional, the wizards from Rochester have brought the layer count down from 12 to 9 and reduced the overall thickness by 20 percent.”

Ektar 25 contains five image recording layers: single blue, fast and slow green, and fast and slow red utilizing second-generation T-grain, but as we’ll find out in a bit, not entirely T-grain in structure.

While the film itself was an innovation, the name Ektar was actually borrowed from high-end lenses Kodak produced between the 1930s and 1960s.

Kodak would quickly and boldly claim Ektar 25 to be the world’s sharpest color print film.

Modern Photography magazine would be quick to prove or disprove this claim, and did several comparisons of the film, beginning in January 1989 with a comparison to Kodacolor Gold 100 in 35mm and 120. You heard that right: Ektar was being tested against medium format film for its sharpness. A comparison was also done against Kodachrome 25.

“The new film, which will shortly be available – and only in 35mm format – is intended more for the serious amateur than the pro, according to Kodak. A professional version, which will debut later this year, will feature all of the same fine characteristics,” says Modern Photography.

The article states that to get the most out of the film you should use a super sharp lens, medium to small apertures, plenty of light, and seriously consider a tripod.

The word grainless is tossed around again, and a better explanation of the structure is given: That the green layer is 100% T-grain, the blue layer is a combo of T-grain and cubic and the red layer is total cubic. The cubic grains are combined with T-grain to maintain the film’s sensitivity to light.

In the comparison, there are some color differences, stating the reds are slightly dark, and in terms of sharpness, Ektar 25 is in the same league as medium format Kodacolor Gold stating “Ektar 25 has the edge!”

Not everyone was impressed though. Bob Schwalberg of Popular Photography called Ektar 25 in his commentary “Critical Focus” in February 1989 “less-than-pedestrian”.

“I’m not much impressed,” says Schwalberg. “This slow speed wonder reminds me of the time I explained some new high-speed lens designs to a very famous photographer, who interjected: ‘In other words, they’re making the lenses sharper.” When I agreed that this was so, he then asked: “I wonder why they do this. Do they think that it will reveal more truth?”

Schwalberg goes on to say that 100 speed films should be as low as you need to go, and he’s not willing to pay the cost of Ektar 25, at the sacrifice of two full stops of emulsion speed. What he’s referring to is the 25% higher price tag than Kodak’s other color films, like their Gold line.

Our critical thinker at Popular Photography didn’t completely drag the film through the dirt, though, and leveled his opinion with this during his wrap-up:

“However, if you’re the type of photographer who takes time with light readings; doesn’t mind shooting with a tripod; has top quality lenses, and likes to make enlargements, this is definitely the film for you.”

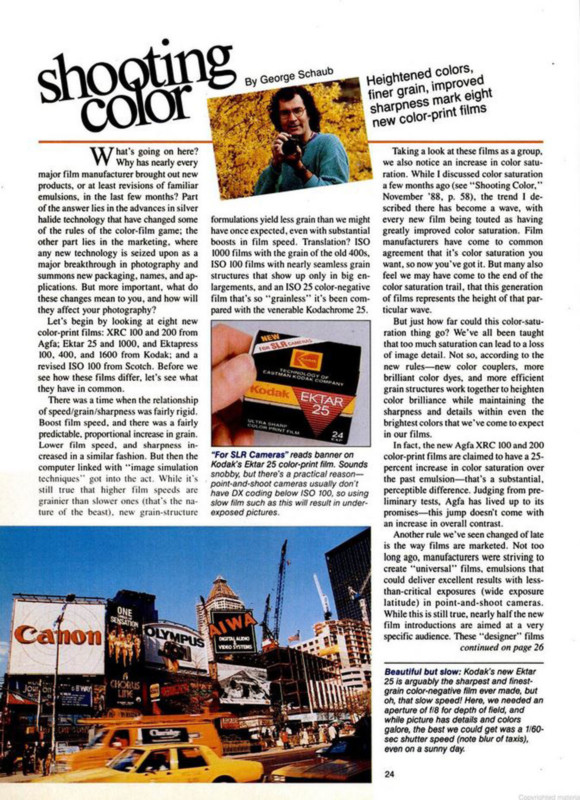

The idea of a film “For SLR Cameras” seems kind of pretentious, but writer George Schaub gives a more practical reason for Kodak’s statement on the box in the same issue: “Point and shoot cameras usually don’t have DX coding below ISO 100, so using slow film such as this will result in underexposed images”

Schaub called the film “beautiful but slow” showing an example of a street scene where f8 was required for depth of field but could only manage 1/60, showing the blur of the taxis. Now, I’m sure he’s just showcasing that there isn’t much of a choice here, but personally, I want to see the cars moving otherwise they look parked in the middle of the road.

In an article by the editors of Popular Photography, also released in February 1989, they state that the “true beauty of this film is revealed with larger than 11×14 print size.”

In an exposure test, we discover that 2 stops underexposed will make things muddy but if you want to tame contrast you can underexpose by 1/3 of a stop. Going two stops over shows how little latitude the film has and the chart demonstrates highly saturated color and accurate rendition of greys. Also, while it’s close to Kodachrome 25 in terms of sharpness, it doesn’t quite beat it.

In March of 89, Petersen’s Photographic showcased Ektar 25 by using it for their cover photo. Also featured in the issue is an article by Jack and Sue Drafahl titled: “King Kodachrome, Make Way for the Queen.”

“Instead of improving a well-established film and making it even better, Kodak introduced a brand-new film. The last time Kodak had an ISO 25 color film was in 1942 – Kodak’s first introduction to the color negative world.”

The review spends some time, talking about the technology, mentioned the color-sensitive layers but also mentions something called DIAR, or Developer Inhibitor Anchimeric Releasing. Which are couplers in the film designed to make the edges of solid colors in the film even sharper, allowing little diffusion from one color to another.

One thing I really liked about this review was the mention of the professional applications of the film.

“Special applications such as photo microscopy, medical photography, and super macro photography can now be raised to new standards through the use of Ektar 25.”

An unexpected disadvantage was the grain. They claimed that making small or medium-sized enlargements was next to impossible because the grain was practically invisible. In this photo example, they ended up having to use the specular highlights to focus for the enlargement. As they put it: “what a thing to have to complain about!”

“This film was designed for advanced amateurs. Ektar is not for point and shoot photographers who are looking for a film to correct their shooting mistakes. Ektar does not have that type of exposure latitude. Besides, many of the point and shoot cameras do not even have DX coding down to ISO 25.”

In May 1989, odern Photography did a feature comparison on Fujicolor Reala and included Ektar 25 in the competition. They did both a studio comparison, as well as one under fluorescent lighting. While the bout was between four films, Reala, Kodacolor Gold 100, Fujicolor Super HRII, and Ektar 25, the conclusion was fixed mainly between Reala and Ektar. In regards to Ekar, they had this to say:

“Frankly, we wondered how it achieves its startling results; it does, after all, use a totally different technology than Reala. Basically, Ektar 25 borrows from its faster stablemate, VR Gold 100, employing DIAR couplers, which are time-released in development, permitting a great deal of color correction in the film.”

They concluded with, “While we expect to see Reala as a 100-speed-only film for some time to come, we’d guess that the market will soon demand a 100 speed Ektar. Just a guess folks; don’t run down to your local store for a roll.”

A good guess indeed, as we would see Ektar 100 by 1992.

Modern Photography also did a test on the latitude of Ektar 25 and concluded useful images from 2 stops under to 3 stops over. A little more forgiving than Popular Photography’s assessment.

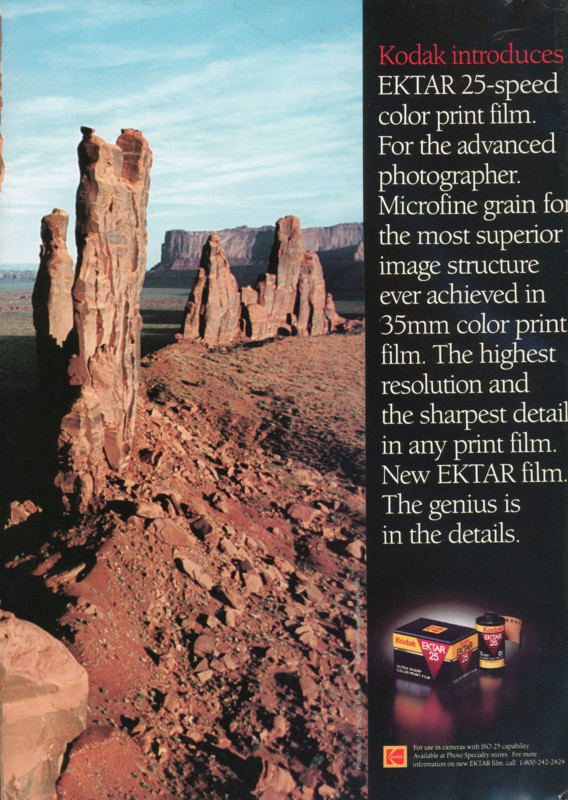

Let’s switch gears for a moment and talk about advertising.

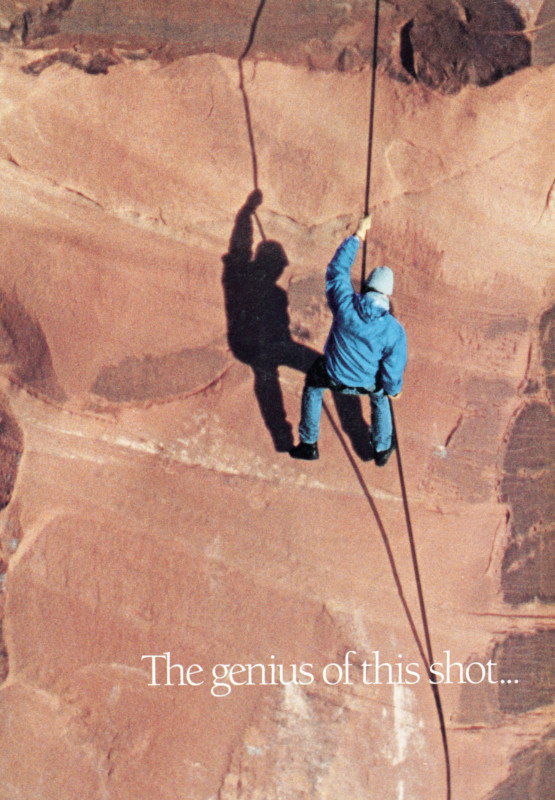

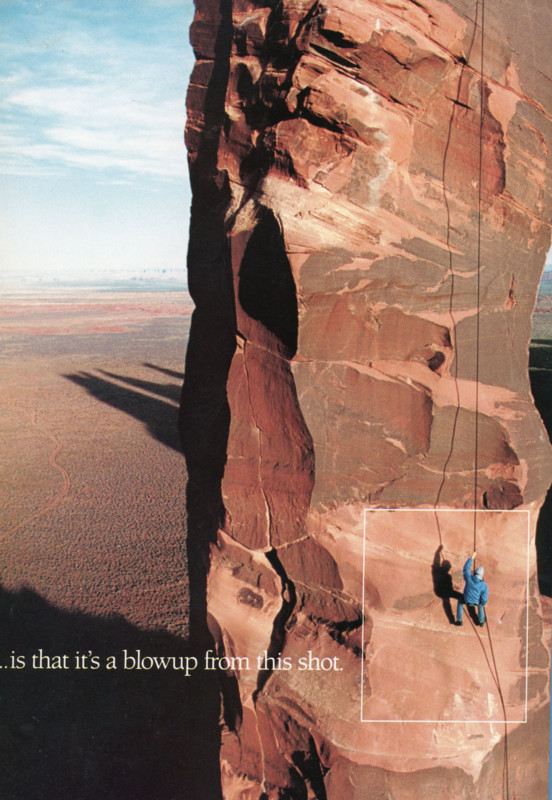

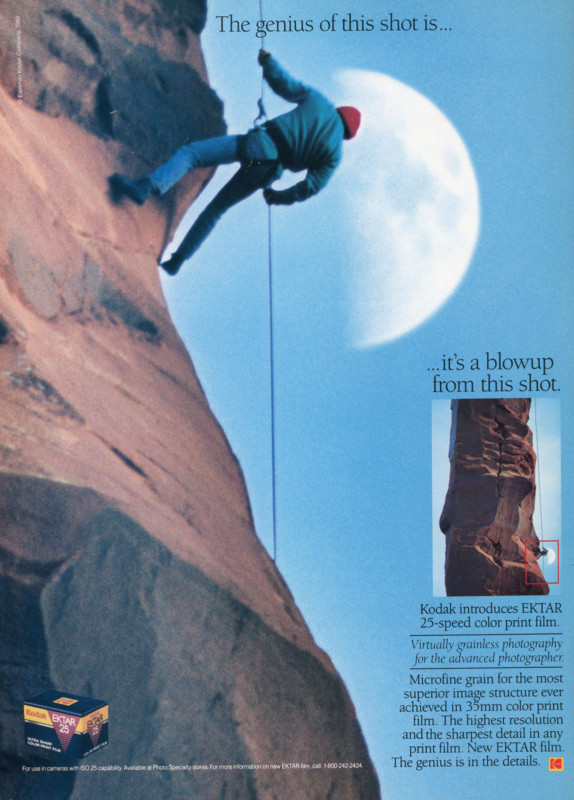

As you may have gathered, the main selling point of Kodak’s Ektar 25 was sharpness, so that was the basis for their advertising campaign. As demonstrated here in the May 1989 issue of Petersen’s Photographic, we are shown a rock climber.

It says “the genius of this shot…” and you turn the page to discover “is that’s it’s a blowup from this shot.” This would be one of a few ads in circulation for their campaign “The Genius is in the Details”

In this campaign, Kodak showed a blown-up portion of the photo, made to look like the total image, and then basically said, gotcha, this is the actual photo.

Here is another rock climber shot,

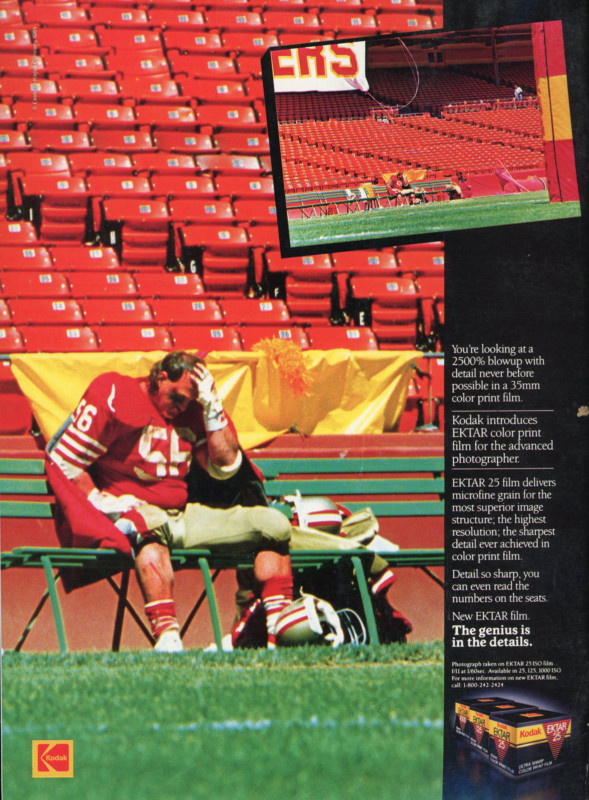

a football player,

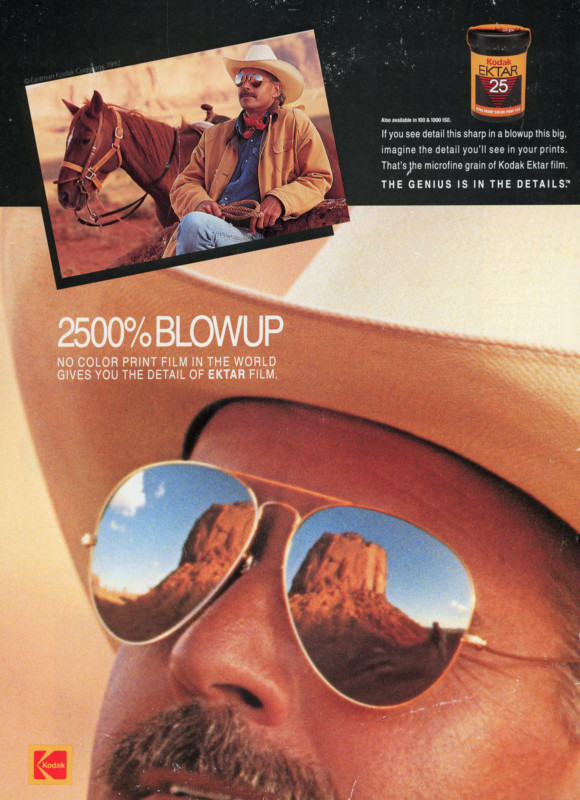

a cowboy,

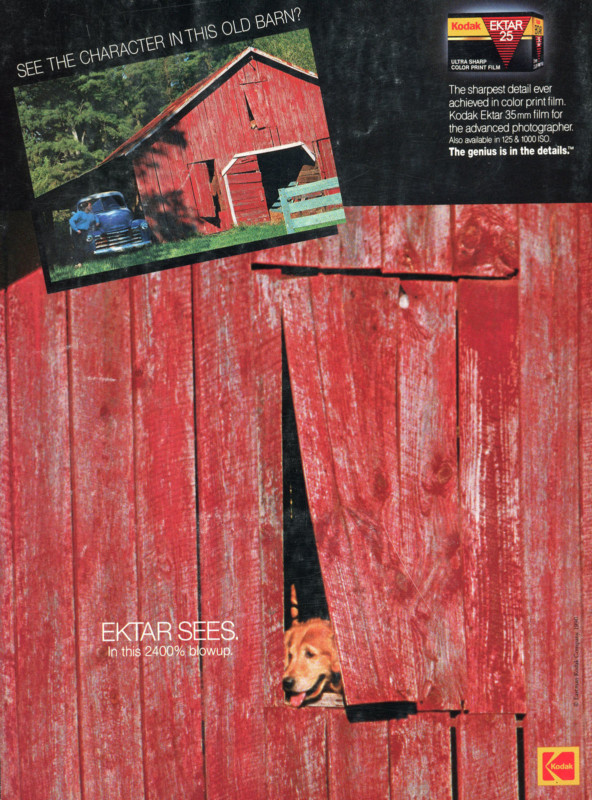

and a dog in a barn.

The magnification ranged from 2400% to 2900% depending on the ad.

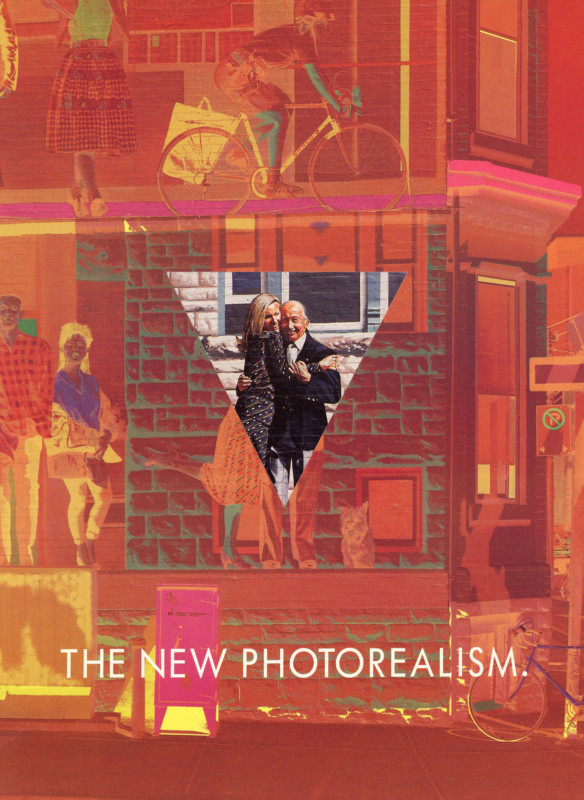

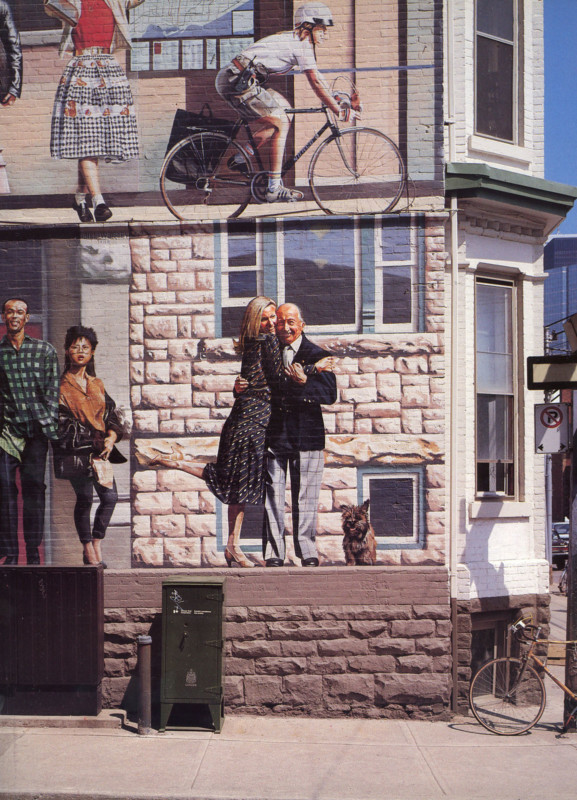

Another ad campaign I came across by Kodak was the tagline “The new photorealism,” which in this first ad shown here, has an actual cut out in the magazine.

That is, there is a triangular-shaped hole in the first page revealing the positive image on the next page.

Kodak again uses the bait and switch, giving you the impression these are real people, and flipping the page reveals it’s part of a wall painting. The ad stated, “Modesty aside, this is the sharpest and finest grain color print film in the world.”

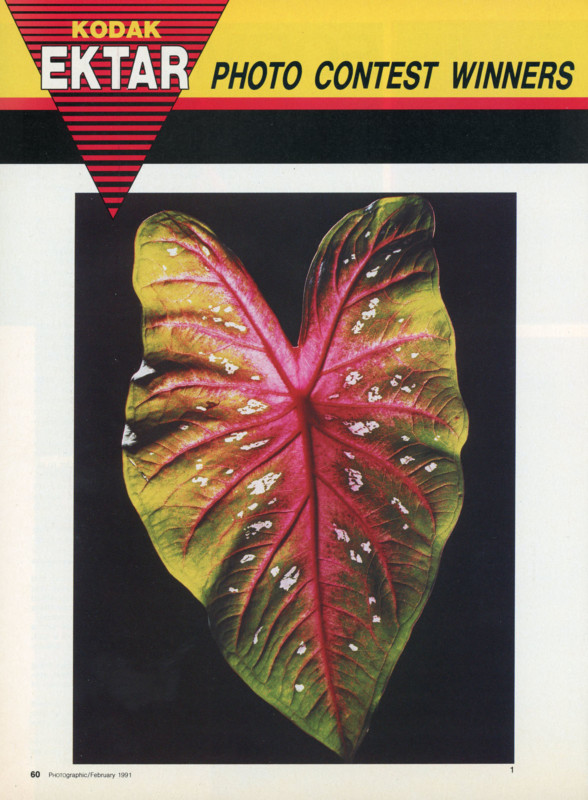

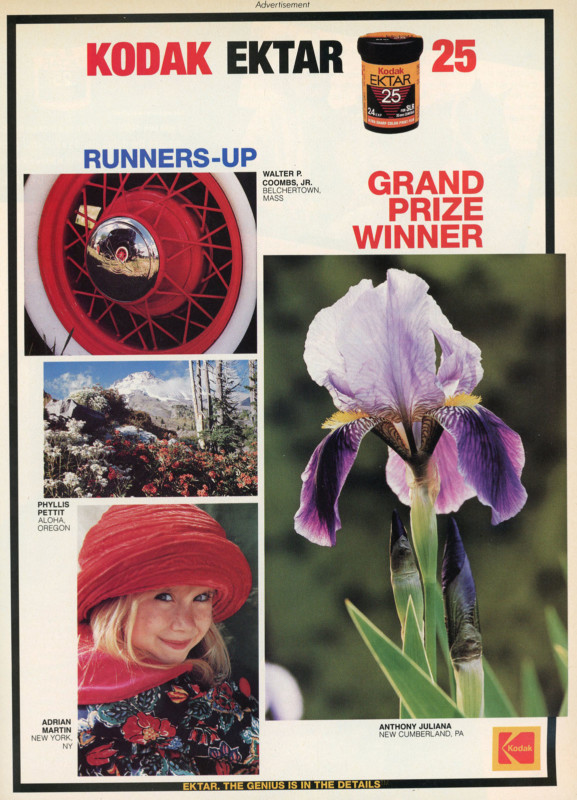

Kodak also held several photo contests for the public in their ad campaigns. As seen here in Petersen’s Photographic and Popular Photography.

In the summer of 1989, Kodak added a 125-speed Ektar to the line and by September Kodak Ektar 25 Professional was introduced. As far as I can tell, the only thing the professional line added was more consistent color from one roll to the next, but they stressed you needed to refrigerate immediately after purchase. “Ektar 25 professional uses the same T-grain and cubic emulsions found in Ektar 25, making it some of the finest color negative film in the world. Because of the critical aging required in the Ektar 25 professional, refrigeration is required until use, allowing consistent results roll to roll.”

It comes as no surprise to any of us that the Ektar line was on the recommended buy list for Christmas 1989 claiming that the “sharpest holiday memories begin right here”

If you told me that 1990 was the golden age of film photography, I would believe you, and to anyone who disagreed, I would show them this poster released with the May 1990 issue of Petersen’s Photographic, which includes 94 films available to consumers.

It’s double-sided and folds out to 16×20. On one entire side is just Kodak films. If this wasn’t the golden age of film photography, it certainly was for Kodak. 41 Kodak films are shown and Ektar’s 25, 25 Pro, 125, and 1000 are shown. But there was another Ektar they were working on under the table and had been toying with ever since the initial release, and in the fall of 1990, Ektar 25 became even sharper, sort of…

In the September 1990 issue of Darkroom Photography, the public is introduced to a medium format version of Kodak Ektar 25 Professional. The opener states that the original 35mm version surpassed Kodachrome 25 in sharpness and fine grain, which is confusing, as other sources said close, but no cigar, like a comparison in February 1992’s Popular Photography which states “While it’s difficult to compare color negatives to positive slides, the amount of detail here is obviously far less than Kodachrome 25”

What some people may have been referring to was that Ektar may have produced a sharper print, as Kodachrome 25 required an inter-negative to be produced, to then make a final print, losing some sharpness along the way.

The article says that Ektar still suffers from a short exposure latitude, and might be even worse. However, the grey scale has improved, compared to earlier batches of the film. So we learn here that Ektar 25 was reformulated at some point in the first two years.

“Ektar 25’s color rendition is its weakest trait, in my judgment. The yellow has been improved since the film’s early days, when it was quite magenta, and now it’s only slightly magenta. Some other colors have also been improved; foliage colors and other shades of green, which originally tended toward the blue, have been brought into line. Ektar 25’s blues continue to be noticeably off in color – a common characteristic of the Kodak Gold films. They veer heavily toward the cyan, and a powder blue sky will somewhat turquoise.”

Also mentioned in the article is the inability to get skin tones right, and that correcting for it will throw everything else slightly off balance.

The article does end on a high note, if not a confusing one stating that “Despite these complaints, I found Ektar 25 to have good overall color.”

In November 1990, Popular Photography Editor Dan Richards reviewed the point and shoot cameras Sigma 35AF and 50AF and in his article Point and Shoot Follies. He talked about how point and shoots are beginning to have DX readings down to ISO 25, and he tests Kodak Ektar with one of these cameras. The same tune is sung here, that you need to also have a sharp lens, and they recommend a tripod, but there is now a place for 25-speed films, like Ektar in point and shoot cameras.

The end of 1990 was a great time to be a photographer. Lots of great cameras, tones of innovation, and Petersen’s Photographic showcased this with their reader’s choice awards. Best 35mm SLR went to the Nikon F4, best medium format went to the Hasselblad 500 c/m, best compact camera was awarded to the Olympus Infinity Zoom 200, and for best color-print film, that award went to Kodak Ektar 25.

“The film is truly extraordinary” states Petersen’s Photographic, “You may find that Ektar is so sharp, it even out resolves some of your favorite lenses!”

Kodak Ektar 25 would be in production until 1997, when it was discontinued, along with its high-speed friend, Ektar 1000. The short-lived 125-speed film would be replaced with a 100 speed in 1991 and is the only surviving Ektar available today. Still, it was that 25-speed wonder that really started it all.

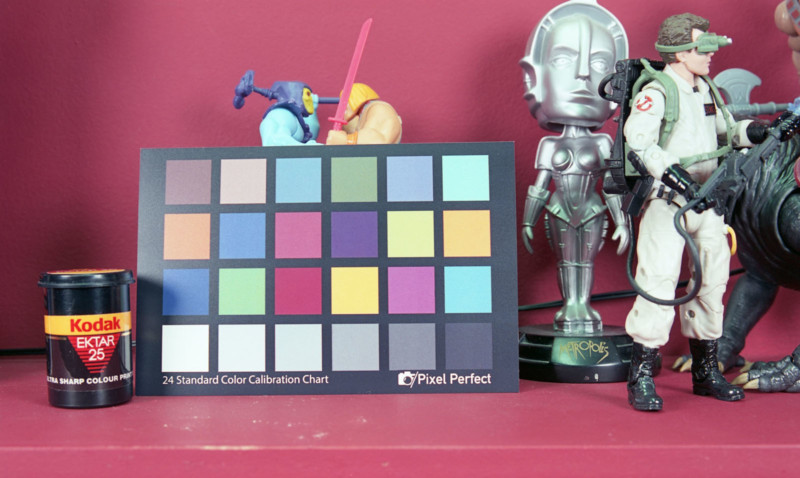

I managed to get a hold of my own roll of Kodak Ektar 25, mailed to me by a generous donor named Al along with a bunch of other films. I was told that this film, which expired in October 1990, was kept cold its entire life, so in theory, I should be able to shoot it at box speed.

Because this film expired in October 1990, and films last a couple of years before they expire, it’s very likely this is one of the first rolls of Kodak Ektar 25 ever produced.

I really like film from this era because of all the little extra details. The inside of the box had little illustrations to help you shoot proper images, a note was slipped into the box, congratulating you on selecting the most advanced color film available from Kodak, and the film canister had its own branding on it.

I really wasn’t sure how well this film would turn out when I shot it. I knew it had been frozen for 30 years, which, let’s be real here, is an incredibly rare thing. Would that be enough though?

The answer is absolutely.

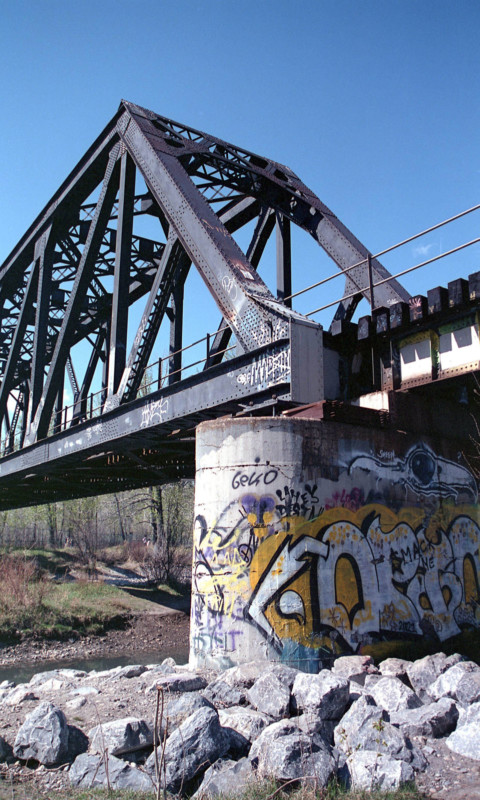

To test the film, I used my Nikon F100 and a 28-105mm lens and went out over the course of a couple of days looking for colorful subject matter. As you’re about to see, the results are nothing short of breathtaking for a 33-year-old color film.

When I scanned these in, I could not believe my eyes. Even though I had taken precautions by overexposing some of my frames, all of what you see here are taken at the proper exposure. No exposure compensation needed. I could not believe it!

I did a test with daylight-balanced lights here in the studio as well and the results speak for themselves. Taken at exposure, I got rich color and beautiful contrast.

Up to 3 stops overexposed, I got flatter, but passable, images.

Underexposed by more than 2 stops, produced unusable images.

Pretty much the same as the tests conducted over 30 years ago.

I think that this really demonstrates the resilience of film. During my time as a photographer, I have used film as old as fifty years and developed mystery film as old as eighty, but that was in black and white, which has a lot more forgiveness. Color film, usually lasts about ten to fifteen years when left at room temperature, if that, and I had shot supposedly frozen color film before with less than stellar results so this roll of Ektar 25 was just astonishing to me, in terms of results.

I’d be surprised to come across another roll like it again. I’m also tempted to take a current roll of something and put it in my freezer and mark it, do not use until 2054.

About the author: Azriel Knight is a photographer and YouTuber based in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find Knight’s photos and videos on his website, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.