Aperture is perhaps the single most important camera setting that every photographer needs to know. Whether you do landscape photography, portrait photography, or anything in between, you have to set your aperture properly in order to capture successful photos. Below, I’ll dive some important terminology — aperture, f-stop, and f-number — and talk about how to use them for your own photography.

1) What is aperture?

Aperture is basically a hole in your camera’s lens that lets light pass through. It’s not a particularly complicated topic, but it helps to have a good mental concept of aperture blades in the first place.

Yes, aperture blades.

Take a look inside your camera lens. If you shine a light at the proper angle, you’ll see something that looks like this:

These blades form a small hole, almost circular in shape — your aperture. They also can open and close, changing the size of the aperture.

That is an important concept! Often, you’ll hear other photographers talking about large versus small apertures. They’ll tell you to “stop down” (close) or “open up” (widen) the aperture blades for a particular photo.

As you would expect, there are differences between photos taken with a large aperture versus photos taken with a small aperture. I’ll cover those in a moment.

For now, just be sure that you can picture the aperture blades in a lens opening and closing, and you’ll be good.

2) What does aperture do?

Aperture is one of the two components of exposure (along with shutter speed). That means it affects the amount of light that reaches your camera sensor.

This should make sense. Aperture is a lot like the pupils in your eyes. It changes how much light you capture.

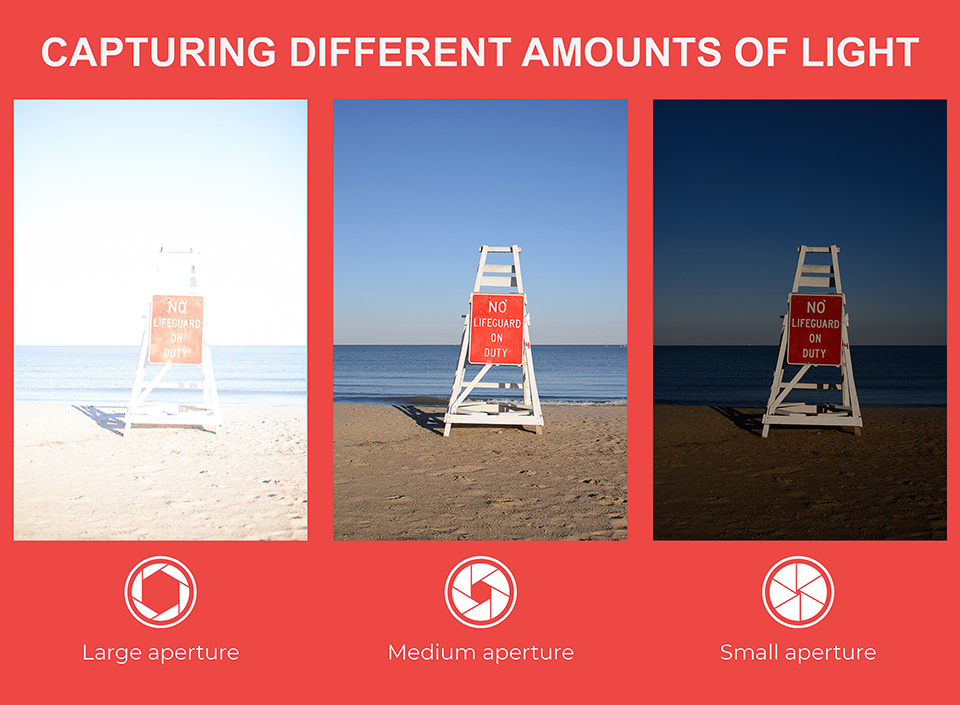

As you can see, a large aperture captures more light than a smaller one. However, that isn’t the only thing that aperture changes.

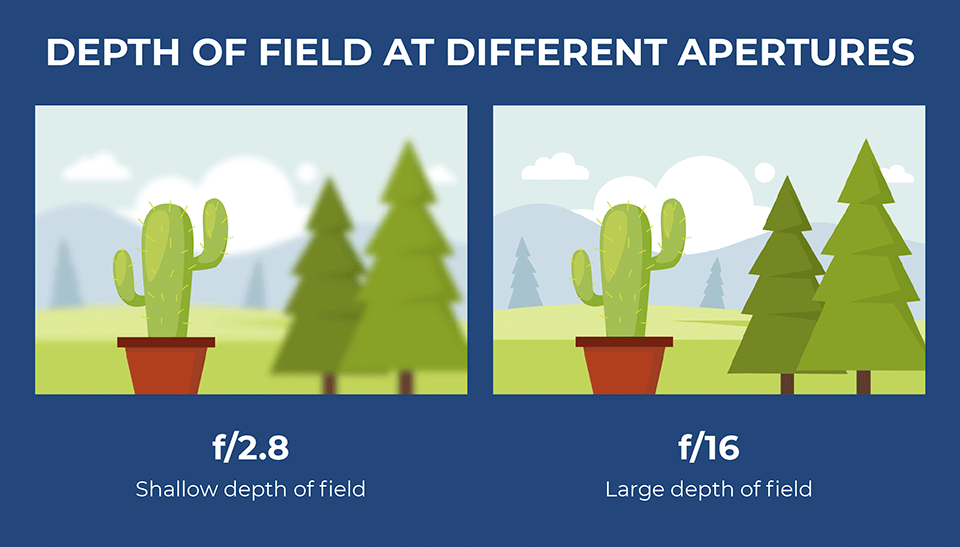

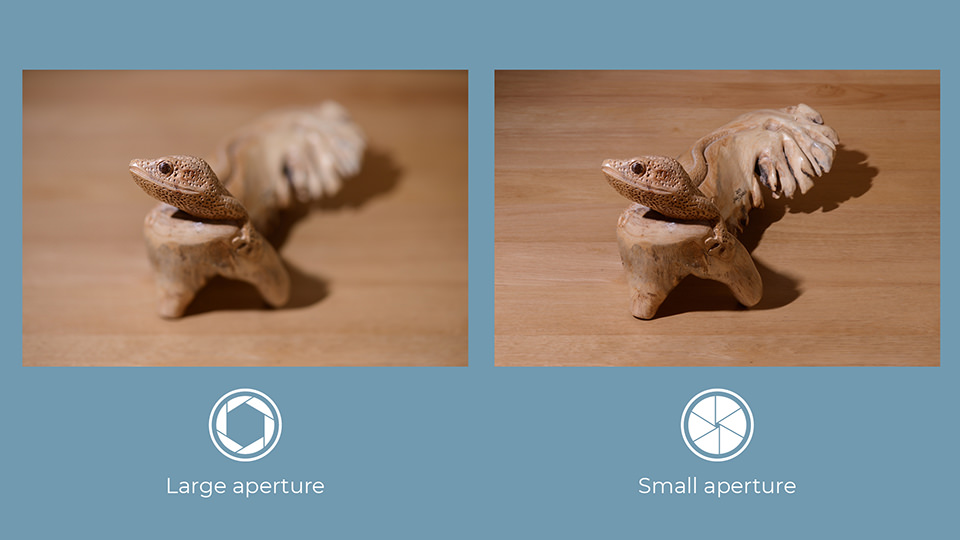

The other most important effect is depth of field — the amount of your photo that appears to be sharp from front to back. For example, the two photos below have different depths of field, which I accomplished by using different apertures:

Adjusting your aperture is one of the best tools you have to capture the right images. You can adjust it by entering your camera’s aperture-priority mode or manual mode, both of which give you free rein to pick whatever aperture you like. (This is why I only ever shoot in aperture-priority or manual mode!)

Before you try it out for yourself, though, there are a few other things you might want to know:

3) What is f-stop?

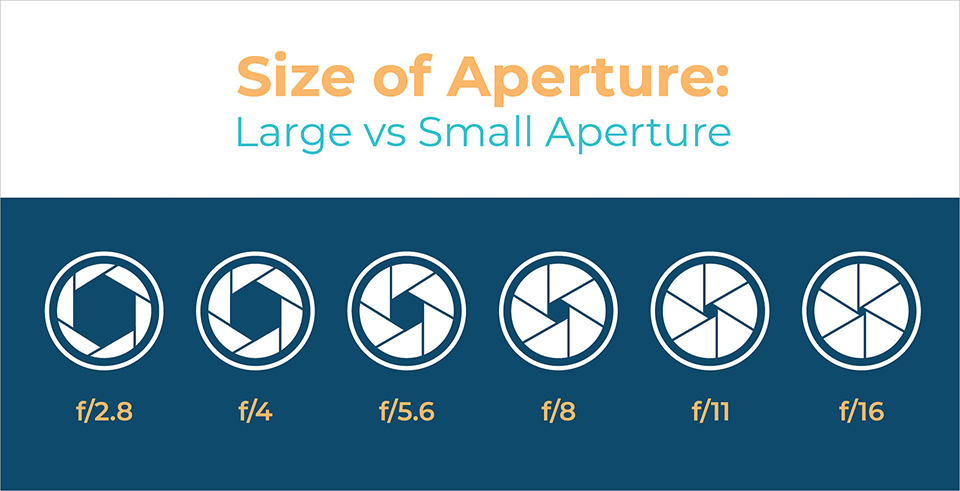

When you change the size of the aperture, f-stop is simply the number that your camera shows you. It is also known as an f-number.

You might have seen this in your camera before. On your camera’s LCD screen or viewfinder, the f-stop looks like this: f/1.8, f/3.5, f/5.6, f/8, f/16, and so on. Sometimes, it will simply be shown like this: f1.8, f3.5, f5.6, f8, f16, and so on.

(I chose those particular numbers just because they’re pretty common f-stops, but they certainly aren’t the only ones. There are plenty of other f-numbers that you’ll be able to set in the field.)

Pretty easy.

4) Why is aperture written as an f-number?

Why is your aperture written like that? What does something like “f/8” even mean?

Actually, this is one of the most important parts about aperture: It’s written as a fraction.

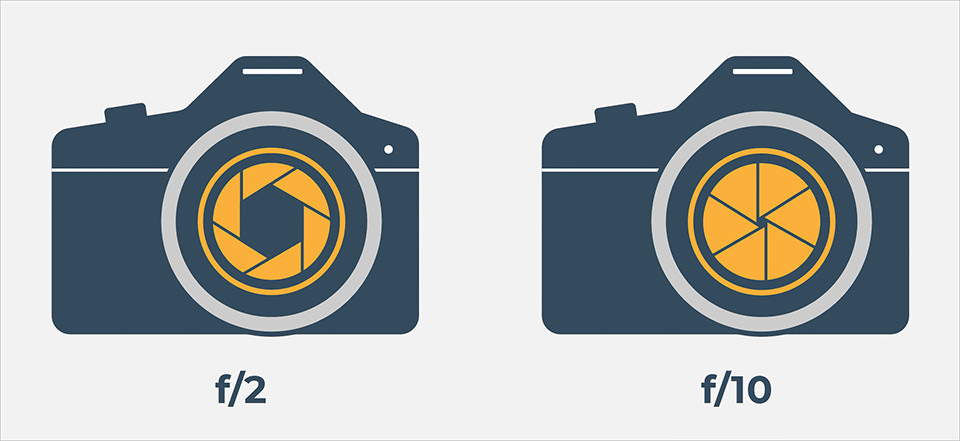

You can think of an aperture of f/8 as the fraction one-eighth. An aperture of f/2 is equivalent to one-half. An aperture of f/16 is like one-sixteenth.

And so on.

Hopefully, you know how fractions work. 1/2 cup of sugar is much more than 1/16 cup of sugar. A 1/4 pound burger is larger than a 1/10 pound slider.

By that same logic, an aperture of f/2 is much larger than an aperture of f/16. An aperture of f/4 is larger than an aperture of f/10.

If you ever read an article online that ignores this simple fact, you’ll be very confused.

Pop quiz: Which aperture is larger — f/8 or f/22?

You already know the answer to this question, because aperture is a fraction. Clearly, 1/8 is larger than 1/22. So, f/8 is the larger aperture.

If someone tells you to use a large aperture, they’re recommending an f-stop like f/1.4, f/2, or f/2.8.

If someone tells you to use a small aperture, they’re recommending an f-stop like f/11, f/16, or f/22.

5) What does the “f” stand for?

A lot of photographers ask me an interesting question: What does the “f” stand for in f-stop, or in the name of your aperture (like f/8)?

Quite simply, the “f” stands for “focal length.” When you substitute focal length into the fraction, you’re solving for the diameter of the aperture blades in your lens. (Or, more accurately, the diameter that the blades appear to be when you look through the front of the lens.)

For example, say that you have an 18-50mm lens zoomed to 50mm. If your f-stop is set to f/10, the diameter of the aperture blades in your lens will look exactly 50mm/10 = five millimeters across.

This is a cool concept. It also makes it easy to visualize why an aperture of f/2 would be larger than an aperture of f/10. Physically, at f/2, your aperture blades are open much wider.

6) Which f-stop values can you actually set?

Unfortunately, you can’t just set any f-stop value that you want. At some point, the aperture blades in your lens won’t be able to close any smaller, or they won’t be able to open any wider.

Typically, a lens’s largest aperture — wide-open aperture blades — will be something like f/1.4, f/1.8, f/2, f/2.8, f/3.5, f/4, or f/5.6.

A lot of photographers really care about the largest aperture (aka “maximum aperture”) that their lenses offer. Sometimes, they’ll pay hundreds of extra dollars just to buy a lens with a maximum aperture of f/2.8 rather than f/4, or f/1.4 rather than f/1.8.

Why is a large aperture so important? I’ll cover that in the next section. However, since people care so much about maximum aperture, camera manufacturers decided to include that number in the name of the lens. For example, one of my favorite lenses is the Nikon 20mm f/1.8. The largest aperture it offers is f/1.8.

If you have a 50mm f/1.4 lens, the largest aperture you can use is f/1.4.

If you have an 18-55mm f/3.5-5.6 lens, it works the same way. At 18mm, the largest aperture you can use is f/3.5. At 55mm, the largest aperture you can use is f/5.6. In between is a gradual shift from one to the other.

Photographers generally don’t care as much about the smallest aperture (aka “minimum aperture”) that the lens allows, which is why manufacturers don’t put that information in the name of the lens. However, if it matters to you, you’ll always be able to find this specification on the manufacturer’s website. A lens’s smallest aperture is typically something like f/16, f/22, or f/32.

7) Letting in the light

I mentioned earlier that aperture blades are like the pupils in your eyes, and that’s a very useful analogy if you’re still trying to understand things.

When it gets dark outside, the tiny muscles in your iris will cause your pupils to dilate (increase in size). This, of course, lets in more light. It’s why we can see things surprisingly well even at night.

Aperture is exactly the same!

A large aperture opening — something like f/2 — will let a ton of light pass through your camera lens and get captured by your sensor.

A small aperture opening — something like f/16 — will block most of the light passing through your lens, resulting in a photo that is much darker.

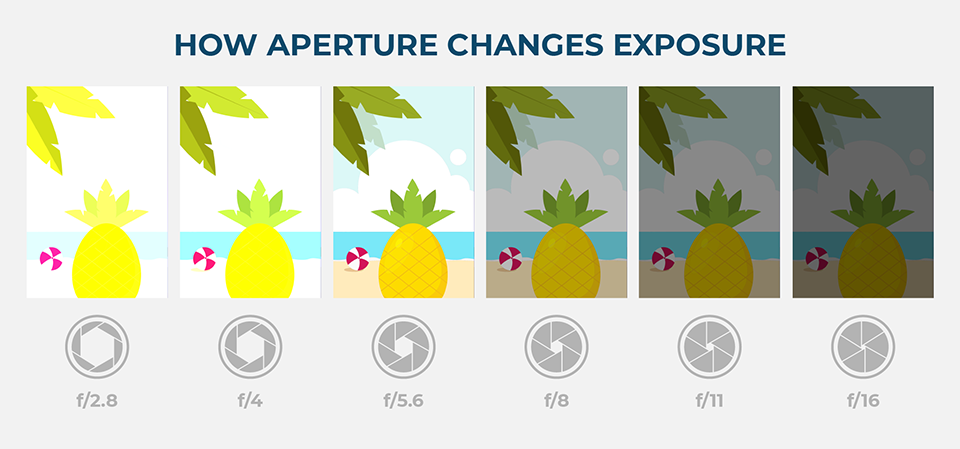

Here’s an illustration to represent how aperture size changes exposure:

Hopefully, you find this diagram helpful. However, there’s one problem: It makes it seem like you should always use an aperture of f/5.6!

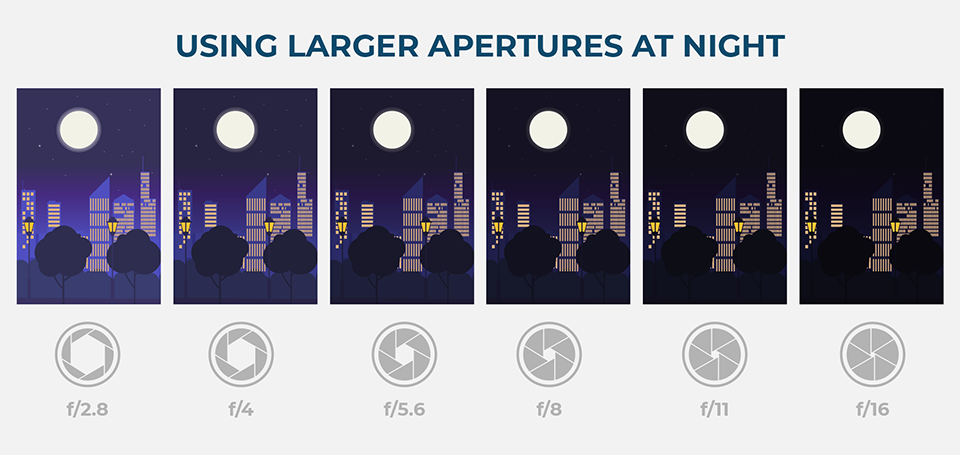

In the real world, that certainly isn’t true. Say, for example, that it’s very dark outside. In order to take a photo with the proper brightness, you may need to use a large aperture, just like a large pupil in your eye — something like f/2.8:

Pretty easy.

The more you practice setting the right f-stop in the field, the more intuitive it will become. If you’re just beginning to learn about aperture, it may help to print the diagrams in this section and use them when you’re taking pictures.

8) Depth of field

Along with the amount of light that your aperture allows, it has one other huge effect on your photos: depth of field.

I always find that it’s easiest to understand depth of field by looking at photos, such as the comparison below. In this case, I used a relatively large aperture of f/4 for the photo on the left, and I used an incredibly small aperture of f/32 for the photo on the right. The differences should be obvious:

This is very interesting! As you can see, in the f/4 photo, only a thin slice of the lizard’s head appears sharp. The background of the photo is very blurry. This is known as depth of field.

You can think of depth of field as a glass window pane that intersects with your subject. Any part of your photo that intersects with the window glass will be sharp. The thickness of the glass changes depending upon your aperture. At something like f/4, the glass is relatively thin. At something like f/32, the glass is very thick. (Also, depth of field falls off gradually rather than dropping sharply. So, the window glass analogy definitely is a simplification.)

This is why portrait photographers love f-stops like f/1.4, f/2, or f/2.8. They give you a pleasant “shallow focus” effect, where only a thin slice of your subject is sharp (such as your subject’s eyes). You can see how that looks here:

On the flip side, you should be able to see why landscape photographers prefer using f-stops like f/8, f/11, or f/16. If you want your entire photo sharp out to the horizon, this is what you should use.

9) What is the aperture scale?

Here’s the aperture scale. Each step down lets in half as much light:

- f/1.4 (very large opening of your aperture blades, lets in a lot of light)

- f/2.0 (lets in half as much light as f/1.4)

- f/2.8 (lets in half as much light as f/2.0)

- f/4.0 (etc.)

- f/5.6

- f/8.0

- f/11.0

- f/16.0

- f/22.0

- f/32.0 (very small aperture, lets in almost no light)

(These are the main aperture “stops,” but most cameras and lenses today let you set some values in between, such as f/1.8 or f/3.5.)

If you’d prefer to see that information in a chart, here you go:

| f/1.4 | f/2.0 | f/2.8 | f/4.0 | f/5.6 | f/8.0 | f/11.0 | f/16.0 | f/22.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very large aperture | Large aperture | Large aperture | Moderate aperture | Moderate aperture | Moderate aperture | Small aperture | Small aperture | Very small aperture |

| Lets in a huge amount of light | Half as much light | Half as much light | Half as much light | Half as much light (a very “medium” aperture) | Half as much light | Half as much light | Half as much light | Half as much light (by which point your photos are very dark) |

| Very thin depth of field | Thin depth of field | Thin depth of field | Moderately thin depth of field | Moderate depth of field | Moderately large depth of field | Large depth of field | Large depth of field | Very large depth of field |

Usually, the sharpest f-stop on a lens will occur somewhere in the middle of this range — f/4, f/5.6, or f/8. However, sharpness isn’t as important as things like depth of field, so don’t be afraid to set other values when you need them. There’s a reason why your lens has so many possible aperture settings.

10) Other effects of aperture

I wrote another article that dives into every single effect of aperture in your photos. It includes things like diffraction, sunstars, lens aberrations, and so on. However, as important as all that is, it’s not what you really need to know — especially at first.

Instead, just know that the two biggest reasons to adjust your aperture are to change brightness (exposure) and depth of field. Learn those first. They have have the most obvious impact on your images, and you can always read about the more minor effects later.

11) Conclusion

Hopefully, you now have a good sense of aperture and the ways it affects your photos. To recap:

- Aperture is a hole in your lens that lets light pass through. F-stops (aka f-numbers) are the numbers that you’ll actually see on your camera or lens as you adjust the size of your aperture.

- A “small” aperture simply means that the aperture blades in your lens are closed quite a bit. A “large” aperture means that the blades have a very wide opening.

- Since f-stops are fractions, an aperture of f/2 is much larger than an aperture of f/16.

- Your lens has a maximum and minimum aperture that you can set. For something like the Nikon 50mm f/1.8G lens, the maximum aperture is f/1.8, and the minimum aperture is f/16. You can’t set anything beyond that range.

- Just like the pupil in your eye, a large aperture lets in a lot of light. If it’s dark out, and you don’t have a tripod, you’ll want to use a large aperture (something like f/1.8 or f/3.5).

- Aperture also affects the depth of field in a photo — how much of the image appears to be in focus. Large apertures like f/1.8 have a very thin depth of field, which is why portrait photographers like them so much. Landscape photographers prefer using smaller apertures, like f/8, f/11, or f/16, to capture both the foreground and background of a scene as sharp as possible at the same time.

- There are other effects of aperture, too, but exposure and depth of field are generally the most important.

That’s it! If you understand these seven bullet points, you’ve got the basics of aperture.

Of course, putting everything into practice is another matter. Even if this entire article makes sense for now, you’ll still need to take hundreds of photos in the field — or, more likely, thousands — before aperture becomes completely intuitive.

Luckily, you have the building blocks. Aperture and f-stop aren’t complicated topics, but they can seem a bit counterintuitive for photographers who are just starting out. Hopefully, this article clarified some of the confusion, and you now have a better understanding of the fundamentals of aperture.