Announced at a press conference in June 1989 in Bar Harbor, Maine, the Canon EOS-1 was a 35mm SLR meant to be a turning point in professional cameras.

Canon did away with traditional controls in favor of a push-button system, utilized ultrasonic motored lenses, and added an LCD display to a fiber-reinforced polycarbonate body. Meant to be a replacement of Canon’s long-time champion, the F1, The EOS-1 was the new flagship, and it took a lot of risks.

The EOS-1 would be among the top picks in photography magazines for 1990, 1991, 1992, and 1993.

In August 1989, Petersen’s Photographic published Canon’s announcement of the EOS-1. Though no price had been revealed at this point, the public knew that it would have five metering modes, a max shutter speed of 1/8000th of a second, a flash sync speed of 1/250th of a second and be able to shoot 2.5 frames per second.

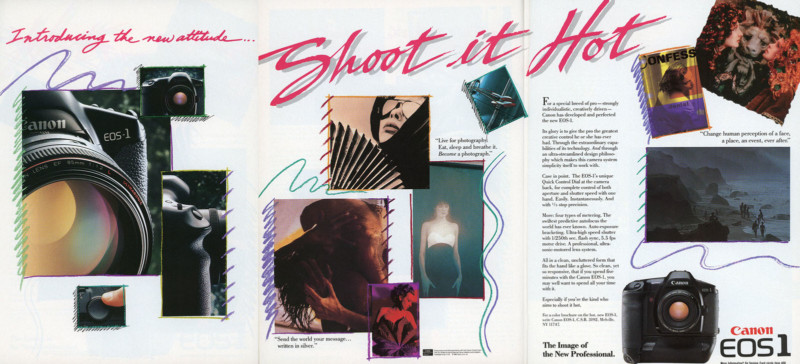

The earliest ad I found was in September 1989’s issue of American Photographer. It’s a colorful three-page ad that would be one of a theme of ads with the suggestion: “Shoot it Hot”.

“Live for photography. Eat Sleep and breathe it. Become a photograph.”

“Send the world your message…written in silver.”

The ad says you’ll experience “The swiftest predictive autofocus the world as ever known,” mentions the features like auto-bracketing and the ultra sonic-motored lens system, and promises all this in “a clean, uncluttered form that fits the hand like a glove. So clean, yet so responsive, that if you spend five minutes with the Canon EOS-1, you may well want to spend all your time with it; especially if you’re the kind who aims to shoot it hot.”

The ad ends with the bold statement: “The Image of the New Professional.”

Another ad in the same issue claims that “Never before has the professional photographer had so much control,” and mentions the “unique rear-mounted ‘Quick Control Dial’,” which would become a staple with Canon SLRs.

In addition to these ads was a full review by Russel Hart. Hart explains that autofocus SLRs have only been around for five years at this point, if that gives you an indication of the groundbreaking nature of the Canon EOS-1.

The direct competition of the time was the Nikon F4, a well-loved model, with more traditional styling, and as Hart points out, “while virtually any previous Nikkor lens can be used on the F4, none of Canon’s manual focus FD lenses can be mounted on the EOS-1. This makes the camera just as much of a financial leap for pros shooting with Canon’s top-of-the-line F1 or T90 as it will be for newcomers.”

In case you didn’t know, Canon had recently abandoned its FD mount almost overnight. The company introduced the autofocus system through EF lenses, and that meant every lens they made before 1987 was unusable on the new system, and many people were upset. Especially those who had purchased the aforementioned cameras, like the T90, only released three years previously.

Hart admits though that the autofocusing is so quick and quiet, it’s “a little unnerving”

Hart spends a little time talking about how a couple of features were borrowed from the Canon T90, including a sort of hidden door, with more button-activated features inside, but his favorite was the custom functions menu. Eight custom functions in all, like canceling the auto rewind, leaving the film lead out when rewinding, overriding the DX coding, and swapping the functions of the main and quick control dials.

The EOS-1 introduced some new things for photographers as well.

“The camera is the first, in fact, to offer shutter-priority auto exposure in third stop increments, and the weird numbers take some getting used to. It’s a little disorienting to get three-, four-, six-, and eight-tenths of a second of either side of the usual half, and you’ve probably never heard of f/7.1”

Popular Photography’s Herbert Keppler also chimed in the same month, saying “Watch out Nikon F4, here’s Canon’s answer, a professional EOS-1”

“Unlike the all-metal Nikon F4 with its control dials, rings, and levers, EOS-1 controls are all electronic, and Canon has trimmed its weight by using a single die-cast metal lens mount, mirror box, and film-plane unit bonded to a fiber-reinforced polycarbonate body,” says Keppler.

Popular Photography’s review echoes the same thing about the autofocus, and that it’s faster than any other, giving an example that with a 50mm lens, you can focus from infinity to 18 inches in 1/3 of a second. Keppler also calls the Quick Control Dial a “major innovation for improved camera handling.”

Though the camera was intriguing for Popular Photography, it wasn’t without its faults. The eight custom functions required you to have your manual with you to translate, the lack of compatibility with older lenses was still fresh and hurt people’s wallets, the diminished brightness of the finder information panel compared to that of the EOS 620, especially in bright light and having to use the custom function menu to switch from evaluative to center-weighted metering.

Despite these shortcomings, the camera was considered a success by Popular Photography.

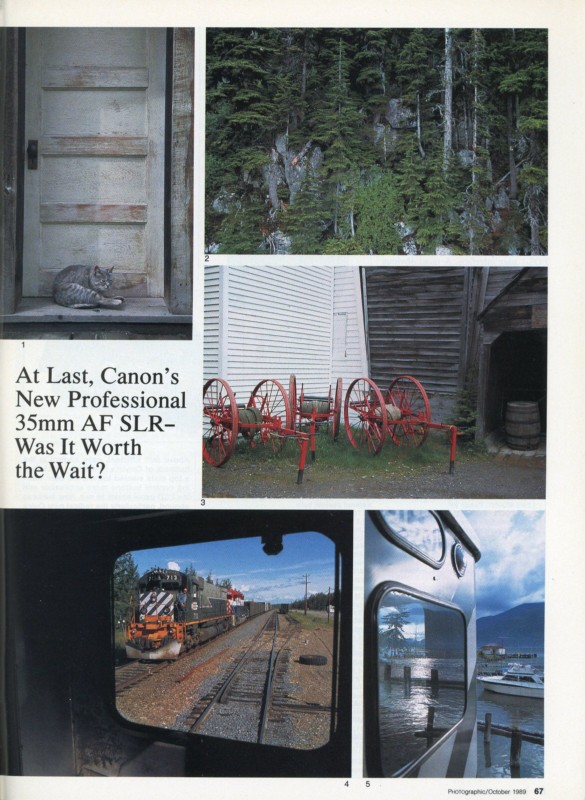

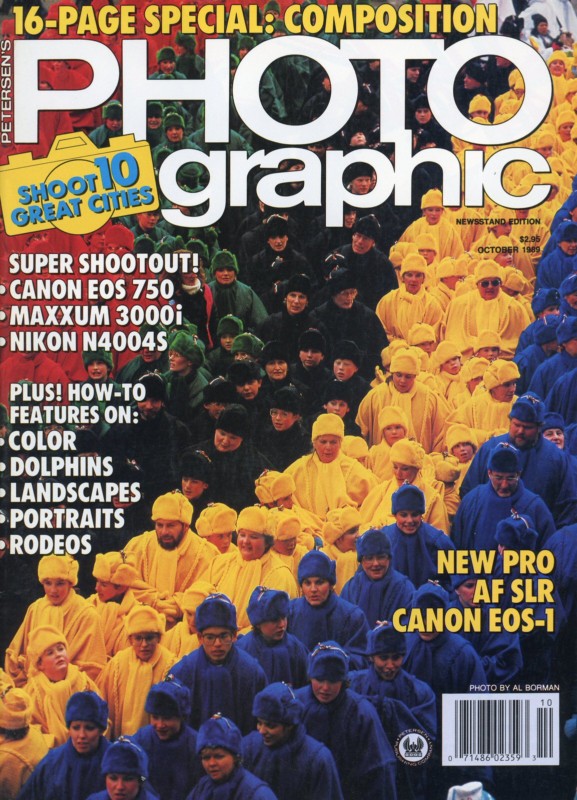

In October 1989, David Brooks of Petersen’s Photographic did a user report on the EOS-1 and tested it in British Columbia.

Other Canon EOS cameras available at this time included the 850, 750, 650, 630, and 620. A price had not been announced for the EOS-1 one as of this review.

The first things that seemed to grab the attention of Brooks were the 100% viewfinder and the quick dial.

The autofocusing system again was one of the EOS-1’s greatest features mentioned.

“In the EOS-1, autofocus has enhanced performance in both speed and sensitivity over the original 620 and 650 EOS models. The new camera utilizes the greater-capacity 12Mhz clock speed microchip main control introduced in the EOS 630, adding a new cross-reference AF sensor so the camera will respond to both vertical and horizontal lines of contrast differences in subjects.

“Combined with the high response speed of the Canon EF design, and with the focus and aperture control drive motors in each lens, plus the virtual instantaneous response of the ultrasonic lenses, the EOS-1 autofocus performance far exceeds traditional manually controlled systems in many important applications.”

I quite enjoyed the review from David Brooks, especially since he went to British Columbia in Canada to test the EOS-1. His review claims that Canon’s EOS-1 created the “highest level of predictable images” and “affords the most secure and comfortable handling I have experienced in a modern 35mm SLR camera.”

David Brooks would revisit the EOS-1 just a couple of months later, in December, with some new lenses including the 85mm f/1.2, a 20-35mm f/2.8, and an 80-200mm f/2.8 — all L series lenses. He also tested a Speedlite, the 430 EZ.

Much of the review goes over the functionality of the lenses and flash but all ties into the EOS-1 in the end. Brooks states, “Now, with an extended complement of lenses, and the new Speedlite 430 EZ, the EOS-1 can be considered a full-fledged professional camera system, in my judgment. Based on the work done for both my initial report and this one, with considerable shooting experience in between, using a varied selection of lenses, I am thoroughly convinced of the capability of the system.”

Canon would continue with its “Shoot it Hot” ad series, with several variations on the theme in 1989 and 1990. The end of 89 would see ads with random photos, or the camera itself.

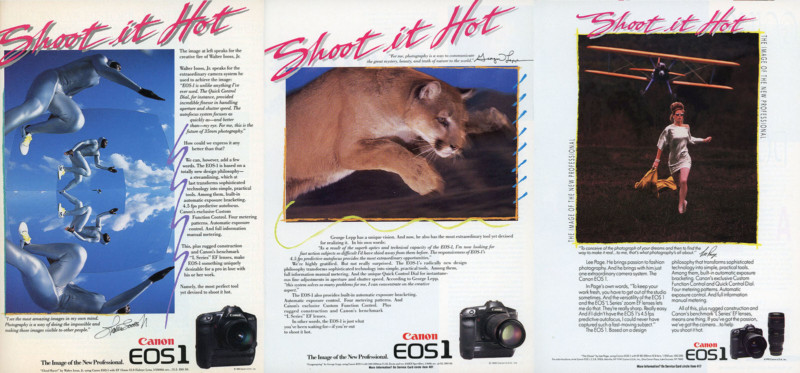

Beginning in 1990 though, there were Shoot it Hot ads featuring professional photographers and their photos taken with the EOS-1. Photographers like Walter Iooss Jr., George Lepp, and Lee Page. Each ad included a quote or two from the artist, their photo, the usual advertising jargon, and even the camera settings for the photo at the bottom.

Lee Page says, “To keep your work fresh, you have to get out of the studio sometimes. And the versatility of the EOS 1 and the EOS L Series zoom EF lenses lets me do that.”

George Lepp states: “As a result of the superb optics and technical capacity of the EOS-1, I’m now looking for fast action subjects so difficult I’d have shied away from them before. The responsiveness of EOS-1’s 4.5 fps predictive autofocus provides the most extraordinary opportunities.”

Of course, that frame rate is with the booster grip.

Walter Iooss Jr. says that “EOS-1 is unlike anything I’ve ever used. For me this is the future of 35mm photography.”

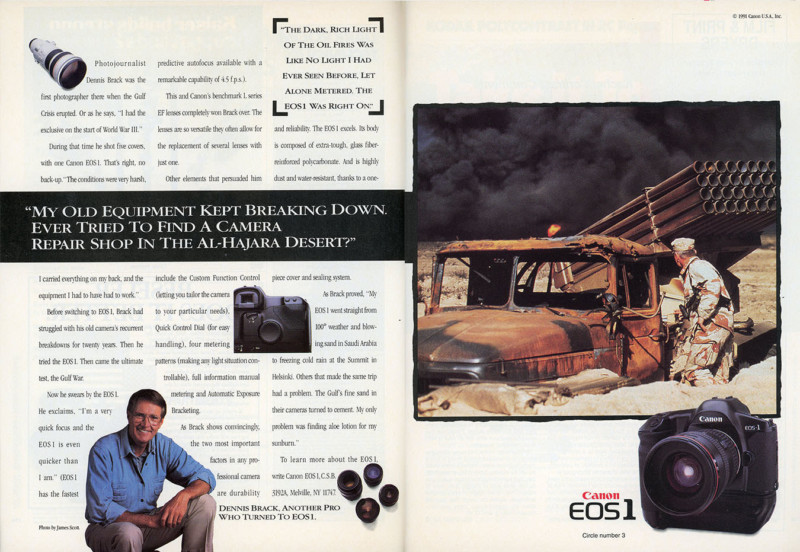

By the end of 1991, the “Shoot it Hot” slogan was dropped, in favor of two-page spreads like this one:

They kept using professional photographers to endorse it, though. The ad featuring David Brack is especially telling of the times, as it features an image taken during the Gulf War. “My old equipment kept breaking down. Ever tried to find a camera repair shop in the Al-Hajara Desert?”

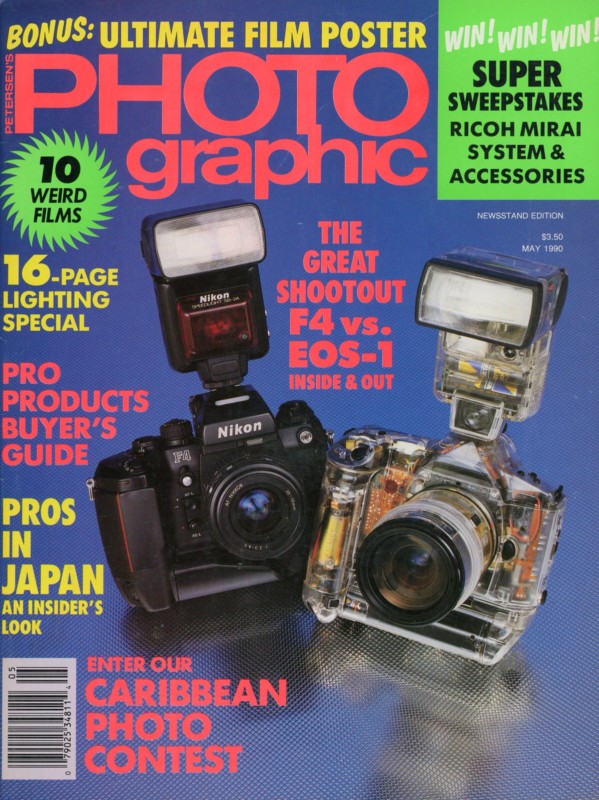

Taking all this in, the innovation, the endorsements, and the glowing reviews, you’d think there was no other camera that could even come close to competing. There was one model though, that was already out and had a strong loyal following. That was the Nikon F4, and in May 1990, Petersen’s Photographic published a nine-page feature on these two industry titans. As seen on the cover here it was the main feature of the issue, showing a transparent Canon EOS-1.

Written by the editors, this in-depth beat-by-beat breakdown first goes over the controls of the camera. The Nikon F4 is, for the most part, seen as a traditional styled SLR with tactile controls like the aperture adjustment on the lens, whereas the Canon EOS-1 is seen as more electronic, with buttons, and an aperture controlled from the camera.

Both cameras offer single and continuous autofocusing. Both offer multi-area, center-weighted average, and spot metering modes, but in addition to that, Canon offers a partial metering mode, in which the camera reads 5.8% of the image. While Canon offers auto exposure bracketing out of the box, Nikon’s F4 requires a special back, the MF 23 or MF 24. Each camera offers flash with automatic metering, known as TTL, and shutter speeds of 30 seconds, to 1/8000 of a second. The Canon EOS-1, being electronic in nature, can set exposure in 1/3 stop increments, while the F4 is limited to full stops.

Many of the differences are small, but one that is glaring of course is at the time of publication, there were only 25 EF lenses, and no backwards compatibility pre-1987, and while Nikon only offered 20 autofocus lenses, they had an autofocus teleconverter called the TC-16A which took 32 manual focus lenses. But the F4 also handled a wide array of manual focus lenses on their own, from decades previous.

The review is meant to be evenly balanced rather than taking sides.

“The long-time pro will probably prefer the F4’s more traditional control. Other photographers may prefer the EOS-1’s control dial and buttons. It took our two 20 year plus veteran photographers a little longer to get used to the EOS-1 than the F4, while our 1980’s photographer actually felt at home with the EOS-1 more quickly than the F4.”

By the beginning of 1992, Canon’s flagship had a price tag of $1,950, body only. Adjusting for inflation, that’s over $3,500, but still not as much as the Nikon F4s, which carried a hefty price tag of $2,550, or over $4,700 after inflation.

In September 1992, Camera & Darkroom Magazine published “A Quiet Revolution, A look at the Canon EOS Phenomenon” by Mike Johnston.

Johnston took an in-depth look at Canon as a company, specifically their transition from FD mount to EOS, the controversy, and resulting innovations.

“When Canon introduced the EOS line in 1987, they immediately earned for themselves, among other things, a bad rap of sorts. The reason was the lens mount capability. The introduction of the new line was news; and the reaction from those heavily invested in expensive FD optics was swift, loud- and, to put it mildly, less than pleased.”

Johnston also says that what really didn’t make the news was the concept that by Canon accepting, what he calls hard knocks, they were taking a step back in order to take two steps forward.

Much of the article talks about the other aspect of Canon, their Original Equipment Manufacturing, or O.E.M.

“If you own a laser printer, for instance, chances are very good that Canon manufactured the actual laser printing mechanism and sold it to the company that built the whole unit.” Johnston related this back to the development of Ultrasonic motors, and how it wasn’t just for Canon’s lenses, but “The reason they could justify the all-out engineering effort required to make this possible is, you guessed it, O.E.M. Canon wants to become the undisputed leader of ultrasonic technology…”

The article also touches on optics, something Canon is still very well respected for.

“Canon’s gotten the jump on their competition in certain areas, such as the use of aspheric lens elements, which are the most effective means to the designer by which to reduce aberrations in large apertures. Leica for instance has indicated it will not produce another run of its Summilux-M 35mm f/1.4 Aspheric, because Aspherics are just too difficult to manufacture.”

Johnston goes on to spend some time talking about the advantages of software and electronics in cameras, as well as the caution of the implications of a camera that can do too much.

“In any event, what is underway at Canon is indeed a revolution, even if it’s a quiet one that’s not making the news every day. What seems indisputable is that the ‘EOS concept’ is beginning to pay off, and that the dividends are looking more and more enticing to many kinds of photographers. So even if you’re not a Canon photographer, it might be wise to keep your eye on them…if only to see which way the winds of change are blowing in the field of 35mm photography.”

If you’re interested in learning more about the canon EOS-1 including a video manual and my personal pros and cons, be sure and check out my video on this camera.

About the author: Azriel Knight is a photographer and YouTuber based in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find Knight’s photos and videos on his website, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.