The children’s brand, which designs and manufactures all its own products, is seeking legal action against the supermarket for selling a baby changing bag which BabaBing claims is a “blatant copy at a quarter of the price”.

Supermarket chains copying the products of small businesses “removes consumer choice” and will result in the “high street dying”, says Nick Robinson, managing technical director at baby brand, BabaBing.

His comments come as BabaBing is set to pursue legal action against supermarket giant Aldi, for its “blatant copy” of a baby changing bag that BabaBing designs, produces and sells.

BabaBing is a West-Yorkshire-based children and baby brand, which sells products such as changing bags, baby bouncers and pushchairs.

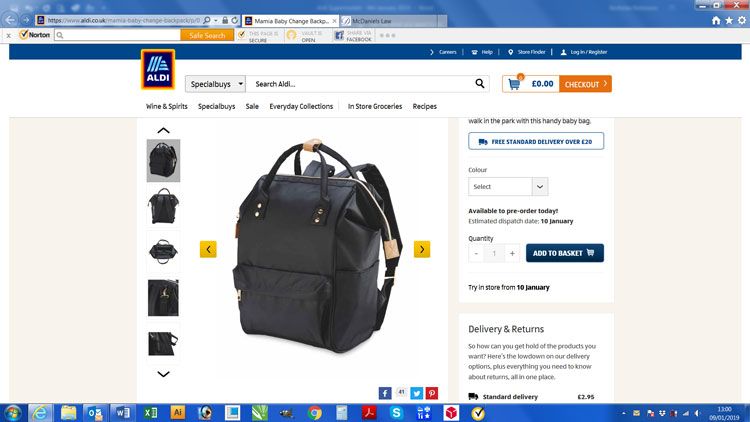

The backpack, which features different compartments and structures such as a fold-out changing mat and bottle holders, retails at £49.99. Aldi’s Mani bag retails at £17.99.

Robinson says that, after purchasing Aldi’s bag at a bargain sale in January, he contacted Aldi to inform the company of the visual similarities between the two bags, saying they had “extremely similar if not identical features”.

He went on to list these, which included the size and shape of the backpack, bottle holder and changing mat, the inner stripe lining of the bag, the brown zipper tabs, internal pockets and front pockets.

Aldi responded by saying that the bag designs “are not a particular breakthrough in the industry”, adding that it had decided to stop selling the bags in future “without any admission of liability” of intellectual property (IP) theft.

“We are not invested in the designs complained of and can do something different next time,” it added.

Aldi also said it “[does] not think that this is a matter which requires legal attention” and offered to discuss working together with BabaBing in the future “as a gesture of goodwill”.

Robinson tells Design Week: “[Aldi] won’t accept liability, when it’s a blatant copy. What has got me is the total arrogance of a big company against a small business.

“Consumers assume that big brands are the champions [because of low prices] but they don’t know about the tens of thousands of pounds that goes into developing products.

“I have no problem with Aldi doing a £17.99 backpack, but I do have a problem with them copying the functionality and features of existing products,” he continues. “We design and produce all of our own products, and companies like Aldi know that small businesses don’t have the financial muscle to do anything if they then get ripped off and sold for a fraction of the price.”

Robinson adds that the impact of this will be small businesses having to shut up shop, and designers being made redundant.

“Previously, we sold a bag we had designed to retailer John Lewis,” he says. “If brands like that see that Aldi are then selling [a very similar product] for a quarter of the price, they might worry that they will lose customers, and so drop us and stop selling our products. This means no consumer choice, and eventually the high street dies.”

He also thinks that copycat designs will “stifle innovation” and ultimately stop designers from creating new products, as they will think there is “no point in doing what they’re doing when they can’t protect themselves”.

An Aldi spokesperson says: “We aim to provide our customers with products of a similar high quality to the leading brands, but at a fraction of the price.

“We sell a wide range of baby products that are hugely popular with parents and we will consider Mr Robinson’s views when planning future ranges.

“We always listen to feedback on our products and would be pleased to meet with [him] to discuss his concerns.”

BabaBing did not apply for registered design rights for the product, Robinson says, and so it relied on the unregistered design rights.

Unregistered design rights last for 15 years after a product is made, and protect the appearance of a product, including shape and structure, contours, lines, colours, texture and decoration. These are an automatic right in the UK.

Registered design rights are a further layer of protection and must be purchased from the UK Intellectual Property Office (IPO) for £60 per design, last for 25 years, and can be renewed every five years. Anyone can view a list of registered designs on the IPO website.

Robinson says he thinks it “probably wouldn’t have made a difference” if BabaBing had registered its bag design with the IPO.

“They probably still would have [copied us],” he says. “[If they have to pay legal fees to us], it’ll be a drop in the ocean to them.”

Dids Macdonald, founder at organisation Anti-Copying in Design (ACID), which campaigns for better design copyright and intellectual property protection, says: “When copying is alleged, major retailers will usually only stop selling the product if there is some basis for the claim.

“‘Without admitting liability’ is a typical comment [they use], so as not to risk their brand reputation and stop their customers thinking they are the bad guys. Producing cheap lookalike products is a fast-track to market by chains, on the back of innovators like BabaBing.”

She says that these “David and Goliath” situations, whereby small businesses lose out to global retailers, are common, adding that it is fairer for both parties if supermarkets commission small businesses to do work for them instead.

“Our message is ‘commission it, don’t copy it’,” she says. “This is win-win all round – the chain benefits, the designer benefits, the UK design industry benefits and it also demonstrates corporate social responsibility, showing ethics, compliance and respect for IP.”

BabaBing is currently seeking legal action against Aldi for the alleged intellectual property theft.

All images courtesy of Nick Robinson.