This article idea is thanks to my husband. Looking at this photo (above) I took on our recent Nicaragua photo tour, he asked “You captured the perfect expression and the perfect moment to fully describe the situation in the photo. Did you shoot that in burst mode?”.

No was the answer.

There has been much discussion lately about the capabilities of modern cameras and post-processing techniques, and what is and is not appropriate. I’ve even been involved in some debates that go as far as to ask when does it stop being photography, when is it too far?

One of those areas open for discussion is the ability to shoot rapid fire, or using burst mode, on your camera. Many DSLRs have the ability to shoot four, six, eight or even ten frames per second. But the questions that it raises are these:

Does it give you better photographs? Does it make you a better photographer at the end of the day?

My answer and opinion is no, it does not!

The Decisive Moment

Henri Cartier-Bresson, considered by many to be the father of photojournalism, is attributed with the phrase, “The Decisive Moment”. Even though he himself never claimed to have coined it, rather an American editor of his book by the same name struggled to translate Bresson’s words so he used the phrase as the book title, and it stuck. Generations of photographers have been influenced by its meaning, and it’s caused countless debates.

Cartier-Bresson said: “To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.” – quoted from Wikipedia

So what does it mean? Well, as the phrase implies it is something special, a fleeting moment in time, an instance that will never occur again. Capturing such a moment is important to creating interest, mood and emotion in your images, especially if you are doing documentary, journalism or photography of everyday life, but even applies to your travel photography and images you take of your own family.

Watch this short video of a chat with the master himself, Cartier-Bresson as he talks about this philosophy. That every moment only ever happens once, and the difference between a good picture and a mediocre one is millimeters.

I talk a lot about the history of photography in my classes and about why it’s important. You can learn a lot by studying the world’s best photographers throughout history. Many have influenced me over the years including Cartier-Bresson. His is a name often heard on many other photographers’ lists too. A few years ago I was lucky enough to see an exhibit of his prints at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC, and the images blew me away. There is a book of that exhibit available called Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century.

So study the masters. Go see exhibits. Do online searches. Learn from them.

To sum up The Decisive Moment – to most photographers it means pressing the button at precisely the right moment, when all the elements come together just so, to make it perfect. That includes: the light, capturing the peak of action, expression, position of the subject, shapes, composition – everything that is part of making a great image. It means making a conscious decision to take the photo at the moment, in that way. It means being ready, knowing your camera and its settings, understanding light, and composition. It means you, the photographer, are in control of whether you go home with a winning image, or a memory card full of duds.

The alternative – “Spray and Pray”

At the opposite end of the spectrum you have “Spray and Pray” which is a common phrase associated with the practice of shooting rapid fire, as many images as possible, and then hoping and praying that you’ve got something good. It is the antithesis of The Decisive Moment mentality, and way of doing things. Even the name sounds a bit derogatory, not like something you actually want to do, right?

This methodology of photography has been popularized with the advent of digital cameras and the fact that it doesn’t cost anything to click away.

When is shooting rapid fire an advantage?

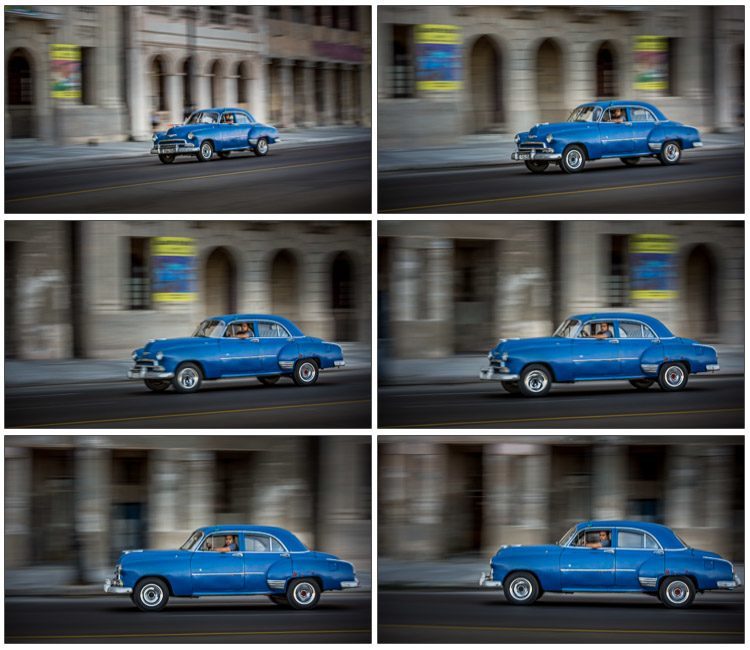

Let’s go back to the question about whether or not shooting rapid fire will result in you having better images. I’ve stated that my opinion is that it will not do that, in most situations, with a few exceptions. In some cases, such as photographing things like sports, doing panning shots, or anything with action like birds or wildlife – shooting in burst mode, and taking multiple frames at a time, will likely help you get some good images.

The series of the old car above was shot in less than two seconds from the first image to the last. Panning is a technique that does require more shots, burst mode and practice. You may have seen this car before in Panning: How to Add a Sense of Motion to Your Shots – give that a read for tips on how to do panning.

This action shot series covers less than nine seconds from first to last image, and was taken by tour participant Bob Dixon. Great work Bob! Without the use of burst mode (high or continuous on your camera’s drive settings) capturing the whole series would not have been possible. When the action is rapidly changing and things moving, this mode can advantagious.

This action shot series covers less than nine seconds from first to last image, and was taken by tour participant Bob Dixon. Great work Bob! Without the use of burst mode (high or continuous on your camera’s drive settings) capturing the whole series would not have been possible. When the action is rapidly changing and things moving, this mode can advantagious.

I photographed these pelicans several times as they swooped low over the waves and by using multiple shots I was able to get them all in a row in the image above. I probably could have gotten the same result shooting single frames, one at a time, but it may have taken longer.

When can shooting mass amounts of images be problematic?

So burst mode has its place, but for most other things you may photograph, I personally suggest slowing down and actually taking less photos. Keep in mind Spray and Pray comes in other forms besides rapid burst mode. Here are a few of examples.

Vacation photos gone wrong

Have you ever been on vacation with your digital camera and come home with a few thousand images? Pretty common now right? If you are old enough to remember what it was like shooting film, that just didn’t happen due to the cost, and photographers were a lot more selective. So of those 1000s of travel photos, how many were keepers? How much work was it to painstaking go through all of them to find the gold? Were you fearful of just hitting delete without carefully examining each image at 100% to check for sharpness first? There’s a pleasure/pain thing that happens in that situation. You experience great pleasure taking the images on your trip, and great pain culling them and perhaps finding out that you missed some great opportunities and didn’t get the shots you really wanted. Can you relate to this scenario?

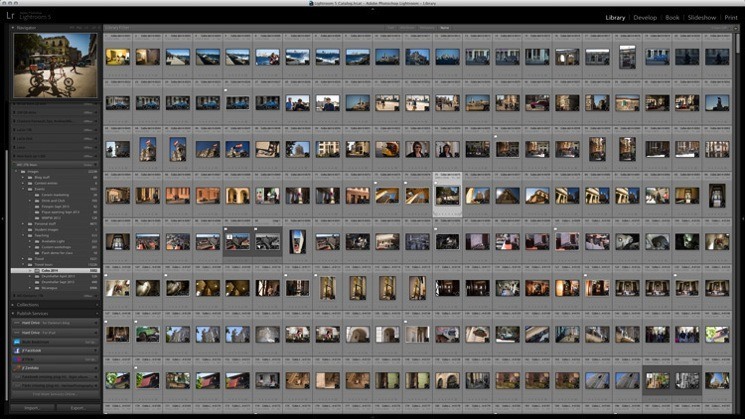

Here you’ll see I have over 3300 images that I took in Cuba in 13 days. That’s nuts! I haven’t had a chance to go through them all yet – in fact I still have images from a six month RV trip where I took over 27,000 images, and I haven’t gone through all those yet either. So you see, I’m guilty of this one too I’m afraid.

Auto-bracketing mess

Auto exposure bracketing (AEB) has also made it easy to shoot three images (one underexposed or dark, one middle and one overexposed of light) just in case you aren’t quite sure what your exposure settings should be. But what if the perfect expression, that peak of action, ends up being the shot that’s too dark and you can’t recover the details? Why not just expose all your images correctly and focus on capturing the moment? If you aren’t confident in your exposures or camera settings, perhaps taking a class would be a good idea. Shooting in RAW will also help as the files carry more information and are more forgiving in this area.

People photography and missing the mark

This trend extends into portrait photography as well. I personally know photographers who set up a group of people, put the camera on the tripod, get everyone in place, and get them to smile. All good so far right? Then they shoot 10-30 images in burst mode of the group, figuring that’s a safe number to get a good expression from everyone. Well, I can tell you that does NOT work. I used to do Photoshop work for a few professional photographers and I’ve been handed a similar set of images and asked to pull three or four different shots together into one (doing head swaps in Photoshop) because there isn’t a single image with everyone’s eyes open or mouth not gaping. Trust me, this happens a lot. Fixing it later in Photoshop is NOT good photography. I used to shoot about five to eight images for groups of people when I used film, and I never had an issue of not getting at least one good, usable image. I waited for the decisive moment each time I pressed the shutter when I could see everyone had a good expression, and I was usually right.

When I photographed this family portrait above I only took about 12-15 photos, all intentionally one at a time. Of those shots (I don’t know exactly how many I took now because I delete all the rejects) they had seven good ones to pick from including these two images. No need to spray and pray. I had an assistant (you could have a friend of family member help you) with me helping with equipment and setup, and also with getting the baby’s attention. I only clicked the shutter when I had some good expressions. You will get a much higher success rate doing it this way than just firing off 20 images in a row and assuming you’ll get some good ones.

Movie mode image grab? Just say no

I’ve never seen any of my students do this but I’ve heard of some photographers shooting in movie mode instead of still frames – and then grabbing one frame of the movie that is the “perfect” shot. I don’t know about you, but that seems at little bit like cheating to me, and WAY more work as well! Why make thing harder on yourself?

How to overcome this problem and take better photos

There are a few things I will recommend for you to practice to conquer this issue of over shooting. Even if this isn’t really an issue for you, try them out anyway and you may find that you still benefit.

- Shoot With Intent

- Work on only pressing the button when you see the action happening. Watch closer and be choosy. Knowing what you’re waiting for is helpful too.

- Look Through Your Eye Cup

- If you use the LCD live view to frame your images and shoot that way, turn it off and look through the eye cup. If you have a point and shoot camera that doesn’t offers an electronic viewfinder in the eyepiece, use it instead of the display screen. What this does it takes away your peripheral vision so you can only see what is in your field of view, what the camera sees.

- Use a Tripod

- Yes, a tripod will slow you down, that’s the whole point. Slow down and be more deliberate with your shots. Check your camera settings, framing, exposure and make sure it’s all perfect before you shoot.

There are many advantages of using a tripod.

- Get Out and Shoot More Often

- Practice, practice, practice. “Your first 10,000 photographs are your worst.” – guess who said that? Henri Cartier-Bresson again. He was a wise man. So it may seem counter intuitive that on one hand I’m saying “shoot less” and on the other hand “shoot more” – but shooting more often helps you become more familiar with your camera, learn about lighting, and hone your photographic instincts.

- Be One With Your Camera

- Until you can change the ISO, focus mode, focus spot, metering mode, aperture, shutter speed and camera shooting mode ALL without removing the camera from your eye, you aren’t one with it yet! See #4 above.

- Make Some Prints, BIG Ones

- Printing your work large (and by large I mean 16×24″ or larger, NOT an 8×12) may seem scary but seeing your images larger will help you grow as a photographer. Images that look great on your camera or computer screen, may not quite stand up to your standards in a large print. It will help you see the areas where you need improvement and give you focus on the which skill you need to work on next.

The images above are of Mike and Kerry in Nicaragua. They were out almost every morning (see #4 above) at sunrise photographing the fishermen bringing in their haul. We affectionately called them “the tripod guys” (see #3 above). But you know what? They got some really great images using those tripods!

So think about what you are shooting before you just fire away. Ask yourself, “Is this the best image I can make of this subject?” and if they answer is no, don’t take the shot. Find a better angle, or come back when the light is better.

Want more information on Henri Cartier-Bresson, check out these books.

Cheers,