Something about the way photographers acclimatize to shooting with film has intrigued me for some time. I think it’s safe to say that film is very much tried and tested — some of the greatest photography pioneers worked with film and were not limited in their ability to create incredible work, which remains relevant.

Photographers looking to get into film now have the entire history of photography and film photography to work with when making their decisions; what film stock to use, how to expose it, how to develop and print it — and yet somehow there is still a learning curve.

Despite often having a goal, style, or “look,” when starting out many photographers will still need to “experiment” and try different things with trial and error and adaptation until they can make film fit for them, or to fit themselves around the film they have chosen.

I think it’s absolutely fantastic that a medium through which so much has been created and communicated continues to be a source of frustration and education in the photography community. It offers something so distinct from the way that experimentation and “trial and error” works with a digital workflow that I really do think it’s worth undergoing.

I know that not only for myself but with many photographers I’ve discussed this with, that successful film photographs do not just represent that image but the entire “film journey” that we have gone on to achieve it. I also know many photographers who begin to shoot with film but after only a few rolls decide it isn’t for them. There can be any number of reasons that this happens, but the one that stands out to me is expectations.

Usually a photographer who decides that film is not for them, no matter how much they might want to make film work for them, is one who has gone into the process with certain expectations — perhaps not even of what film can do but what it ought to do, or what they ought to do with it.

Many photographers have existing digital workflows and perhaps have developed their own “look” which they are capable of achieving digitally but are unable to foist onto film. Alternately they may be buying a specific film stock with the knowledge that certain work was produced on it or that certain photographers swore by it.

I think that there may be some levels of cognitive dissonance at play here; excellent work has been produced on any type of film you’d care to mention, covering almost any “look” you can imagine, but newcomers to film will still look for excuses as to why they aren’t able to produce the results they want. They know it can be done, but find excuses why they cannot.

Whether these expectations come about through being marketed to, or limited access to a “film community”, or simply being under-educated on the specifics, I think that they are damaging, especially when it leads to a photographer deciding to put down film once and for all. It can lead to extra cost, as the photographer shoots numerous “test rolls” without ever really basing sure about what they’re testing beyond a perceived “look” (and so, of course, getting inconclusive results with every frame). It can lead to frustration from lost frames, underexposed or underdeveloped chemistry, or grain levels they aren’t comfortable with. I don’t even know that these issues are unique to film, but that you must wait longer to see the results, which means adaptation takes more time.

I think that this is why photographers who allow themselves to start simply, shoot with consistency, and allow themselves to be led (to an extent) by the strengths and weaknesses of film will have a better time. As with many things in photography there is a positive feedback loop – the more rolls you shoot the more keepers you’ll have, the more you’ll like the film, and the more you’ll understand how it will behave when faced with similar conditions in the future.

After all, how many keepers do most of us have after every 36 frames on digital? If you shoot only one roll and have no keepers, that doesn’t necessarily mean that film itself is the problem; perhaps you were simply uninspired for the duration of that roll.

Quantity aside, I think one of the main struggles with film is obtaining a consistent “look” – especially when, as I mentioned earlier, the photographer is looking to merge their film work with an existing digital portfolio. Many photographers enjoy leaving their film scans “as is” out of an attempt for an undiluted/authentic aesthetic. Others will edit, to the point at which the image looks identical to their digital results. If people are capable and happy with their edits then I don’t think there’s a problem, but when people are struggling then I think they could benefit from a more “purist” approach before trying again when their skill has improved, or they are more comfortable with the tools they are using.

Another thing to keep in mind is the influence of the scanner on the look of the film. Whether using a flatbed, dedicated scanner, or a macro lens on a digital camera, all a scan is is a photo of a photo. When applying your “look” to a film photograph, you are actually editing a digital photograph, or scan, which could have already gone through a number of filters or processed in a certain way. This can create conditions that are unexpected, and I recommend scanning as neutrally as possible before making your own tweaks.

Scanning can also introduce issues that can sour a photographer’s opinion of film as a valid medium. For example, I know a photographer who complained to me about excess grain in their images shot on FP4, which is usually a very sharp, low grain film — it turned out the scanner their lab was using was faulty and producing its own noise that rendered itself onto his images. When he started scanning independently this issue stopped, and he was very happy with the results. Extra grain can also result from over agitation, which is something to look out for. The best results in my images have come from stand developing.

Exposing for film is quite a different process to exposing with a digital sensor, and this can be one of the hardest things to learn. For example, many enjoy the look of very deep shadows, which can be achieved easily digitally by exposing for the highlights – usually enough to eliminate the lower end of the histogram. Film will render dynamic range differently, so sometimes more detail remains in shadows when metering for the midtones, so many who simply underexpose their shots on film are disappointed by the murky results.

It takes a certain degree of care to really execute the exposures you want, but once you know what area to meter for it becomes much simpler. High-contrast lighting was one of the trickiest things for me to deal with and eventually led me to simply overexpose everything, and instead search for images where the action and characters were more inherently interesting than any lighting tricks.

My advice is usually to lean into the strengths of film before trying to bend it to your will. Experiment with the different options and brands, whilst also researching the work of the “greats” to see what they were able to create, and how. There is so much variety in old work, and so much potential for fresh innovation in the way film is used, it shouldn’t be difficult to find something that works for you.

Some people use film in order to have something especially distinct from their main body of work. This is one of the reasons I began with film, as I felt that everything I produced digitally was too “clinical.” Having a collection of film work as a satellite around an existing portfolio can be a breath of fresh air both for the creator and their audience.

I think that starting a project on film is a great way to go, and a great way to have a neat body of work by the end of it which represents not only the subject of your project but your progress with shooting film over time. I know a few photographers who choose to shoot film only for personal or family moments, keeping digital for everything else, and this usually has really wholesome results, as film really does lend that nostalgic touch.

Other advice for beginners is a little more practical but ensure a smooth film experience. Examine and possibly service your mechanical camera before using it for the first time to make sure that potential issues are pre-emptively dealt with — things like light leak, slow shutter and so on. Use a system you are familiar with or can take lenses you already own, or invest in a system you are willing to become deeply literate with. There will be fewer settings/menus to worry about, so focus on the basic functions and spend the majority of your time working on composition, exploration, lighting, or anything separate from the camera itself.

Learn how to read light, and how different films render in different environments. In order to avoid disappointment in early images I’d suggest overexposing by a stop or two when shooting with black-and-white or C41 (slide film should shot dead on at box speed!) – summer is a great time to begin with film because of the availability of light.

I made the mistake of starting to shoot film in the winter. This meant a lot of pushed rolls and discomfort before I was able to fall into a routine and start to fit it around an aesthetic.

It can be tempting to simply go straight to shooting something like Cinestill 800 at night, but more often than not this is not a productive way to start. Instead allow yourself to shoot simply, as casual as you like, in the day with a reasonable ISO (400 is my standard as I can shoot it in any conditions). When you’re comfortable with this then night-time and more experimental stuff will come much easier.

I think that, especially with black-and-white film, if you aren’t getting the results you want it could be more useful to you to expose the film differently than trying a different emulsion. In my experience, the “look” of film depends more on how you expose it than anything going on in the chemistry. As said before, any film can have any number of looks depending on the way it was exposed, the conditions it was shot in, the development process, and so on.

Many photographers choose to work with film because it allows them a more hands-on approach to making their work look and feel the way they want it to, from shooting to printing. I think that some of the newcomers to film might genuinely miss out on aspects of that control if they don’t process their own chemistry, or never print an image in the darkroom. It isn’t an absolute necessity, but I really do recommend following through with a technique to it’s fullest extent, even if it’s just to see what it’s capable of, and how it affects the way you feel about your work.

Be open to allowing film to shift your style and approach to photography overall, and give it longer than the first few rolls to actually form a workflow around the process. It does take time to learn some of the more subtle nuances, as well as to imprint a more personal touch on film images, but (as you can probably tell from the way I talk about it) I’ve found it to be an absolutely worthwhile experience.

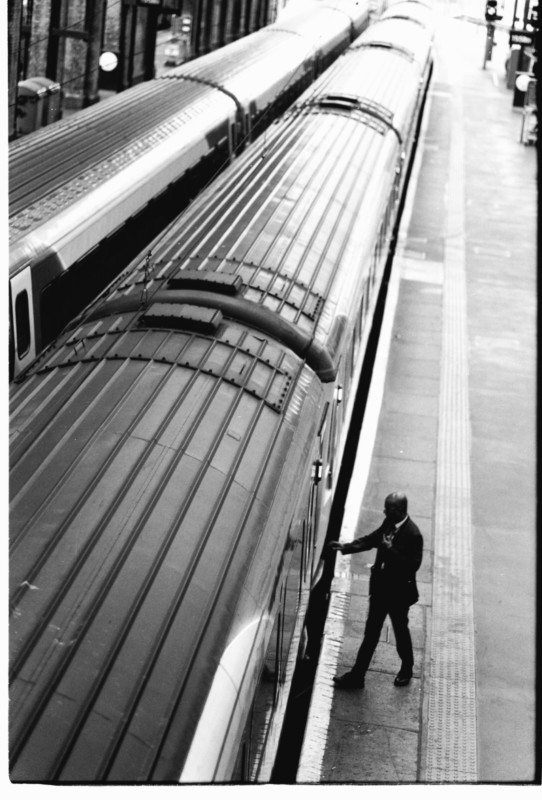

About the author: Simon King is a London based photographer and photojournalist, currently working on a number of long-term documentary and street photography projects. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can follow his work on Instagram and you can read more of his thoughts on photography day-to-day over on his personal blog. Simon also teaches a short course in Street Photography at UAL, which can be read about here.