In the age of digital photography, your monitor is as important as the camera you shoot with or the lenses you use. But as more high-end options hit the market every year, the line between “worth it” and “overkill” is starting to blur. Dell’s new 32-inch 4K HDR PremierColor mini-LED monitor, an elite display by any standard, is helping to draw that line a little bit clearer.

One of the most valuable pieces of “gear” that a professional photographer or video editor can purchase is a color-accurate monitor. The vast majority of your audience will experience your work through pixels, not print, and editing on a crappy monitor is like shooting through a stained-glass viewfinder: sure, you can do it, but you have to keep your guard up the entire time or the final product will look nothing like you thought it would.

When Dell offered to send me their new 4K HDR monitor with 2,000 individually controlled mini-LED dimming zones and a built-in colorimeter (AKA the Dell UltraSharp UP3221Q) for review, I almost said no. When Apple … err … neglected to respond to my request for a Pro Display XDR so I could do a side-by-side comparison, I was almost certain I would say no. Every review starts with a relevant question, and “is this a great monitor?” seemed like a stupid one. Of course it’s great, it costs $5,000. Anything less than “great” would be an insult.

But then I found another, better question, and that question is this: where is the point of diminishing returns? In other words, does this display pack the right combination of features to justify spending $5,000?

In the absence of direct comparison, I wanted to see if the real-world experience of using the pinnacle of mini-LED display technology would convince me that it’s worth spending several thousand extra dollars on features like true HDR performance and 10-bit color.

What is “mini-LED”

First, I should clarify a few of the terms I’ll be using throughout the review, because display terminology is a mess. Broadly speaking, two kinds of displays currently dominate the modern monitor market: LCD and OLED. LCDs use a backlight to shine light through a liquid crystal (LCD) layer, while OLEDs use an organic (OLED) compound that emits its own light.

This is where it starts to get confusing, because all top-shelf LCDs use LED backlights of one form or another, so seeing the term “LED” doesn’t mean you’re dealing with an OLED screen.

LED, mini-LED, and QLED are all technologies used with LCD monitors—they use a backlight—while OLED, AMOLED, and microLED are all emissive displays that do not need a backlight. Finally, TN (twisted nematic), VA (vertical alignment), and IPS (in-plane switching) are all LCD technologies, so when you see that your monitor has an IPS panel, even if there’s “LED” somewhere in the name, know that you’re dealing with an LCD.

To review:

- OLED display = Organic LED, no backlight

- AMOLED display = A special kind of organic LED, no backlight

- microLED display = the future of OLED, no backlight

- LED display = an LCD with a backlight made up of multiple LEDs

- mini-LED display = an LCD with a backlight made of more, smaller LEDs

- QLED display = a type of LCD display with a special “quantum dot” layer between the LED backlight and the liquid crystal layer

- TN, VA, and IPS = the three main types of LCD panel

I won’t dive any deeper, but you can learn more about the pros and cons of each technology here, here, and here.

What we’re dealing with in this review is a 4K IPS LCD display with a backlight made up of 2,000 individually controlled mini-LEDs that are referred to as “local dimming zones.” When they’re not used each mini-LED can be turned off individually, allowing for better contrast because you’re literally turning off that part of the screen when it’s supposed to be black.

Key Features and Competition

There are three LED-backlit IPS monitors that the Dell UltraSharp UP3221Q is mainly competing against in its price bracket and size category: Apple’s $5,000 Pro Display XDR ($6,000 with the stand), ASUS’ $4,500 ProArt PA32UCX, and EIZO’s $5,700 ColorEdge CG319X. All of these use an LED backlight (the ASUS is mini-LED), offer 32-inch screens with at least 4K resolution (Apple is 6K), boast true 10-bit color, cover almost 100% of the DCI-P3 color space, and get bright enough to actually support HDR.

In the case of the Apple, ASUS, and Dell displays, they’ve all earned the VESA DisplayHDR 1000 certification by offering peak brightness of at least 1000 nits, seriously impressive static contrast ratios, and top-shelf color accuracy. In other words: these are true HDR monitors, which can and should be used to edit HDR content if you want to get your money’s worth.

Where the Dell stands head and shoulders above both the Apple and ASUS display is that they managed to pack 2,000 mini-LEDs into the backlight—more than anyone else on the market as of this writing. This outperforms both the Pro Display XDR (which uses 576 regular LEDs) and the ProArt monitor (which uses 1,152 mini-LEDs), and should translate into better dynamic contrast with noticeably less “blooming” when you have a well-defined bright object against a dark background.

Additionally, the Dell—unlike either the Apple or ASUS displays—features a built-in Calman-powered colorimeter. This allows you to calibrate the display on a schedule, using a vast array of calibration targets, whether or not you actually have a computer connected. You can even connect your own colorimeter to a dedicated USB port on the bottom of the display, although I should note that my DataColor SpyderX Elite was not supported, so I still had to use a computer to validate Dell’s claims about color accuracy.

At least on paper, the Dell stacks up very well against its main competition. Assuming it performs as advertised (spoiler: it does), it looks like a steal compared to both the Apple and EIZO displays, and offers plenty of additional features to justify the extra $500 on top of the ASUS.

Real World Review

Design and Usability

The Dell UltraSharp UP3221Q is beautiful but… big. Any 10-bit IPS LCD with this kind of backlight is going to be thick and heavy, and the Dell is no exception—the laws of physics and heat dissipation will not be ignored.

The monitor measures about 1.5-inches thick at the edges, with exhaust vents all along the sides and a somewhat chunky bottom bezel where the built-in colorimeter folds away. The remaining bezels are satisfyingly thin, making for a minimalist “all screen” look, and the back of the display is covered in a thick plastic with a platinum silver finish. The plastic casing saves some weight, but it’s not going to be as solid (or impressive looking) as the aluminum that Apple uses in the Pro Display XDR. Whether or not that really matters is for you to decide.

In terms of ports, you’ve got a full-fledged Thunderbolt 3 connection with 90W power delivery, two HDMI 2.0 ports, a Display Port 1.4, two USB Type-A 3.1 ports, an audio out that does not support headphones, and an additional Thunderbolt 3 port that is limited to 15W of power delivery. Conspicuously missing from a “creator” monitor of this caliber are a true audio pass-through and an SD card slot. That’s pretty disappointing when you consider that my $600 BenQ monitor has both.

Finally, the only input mechanisms built into the display is a recessed power button and a single joystick. Nothing to say here except that a joystick like this is my favorite way to navigate display menus—it’s better than multiple dedicated buttons, and much better than the touch-based “buttons” you’ll find on some displays. I wish everybody would move to this kind of system, even if it’s a bit more fragile than the alternatives.

Color Accuracy and Brightness

From a technical standpoint, the UP3221Q actually outperformed its spec sheet, showing full 100% coverage of the DCI-P3 color space and 94% coverage of AdobeRGB in our measurements—Dell only claims 99.8% DCI-P3 and 93% AdobeRGB. We weren’t able to test brightness claims, but trust me when I say that max brightness (with HDR turned on) is sufficiently retina-burning to keep you from questioning it.

Needless to say, switching from my BenQ SW2700PT—which, admittedly, is showing its age at this point—was like a revelation. In terms of design, resolution, brightness, color reproduction, and color accuracy (DCI-P3), this $5,000 monitor made my old $600 panel look like trash.

I know… you’re rolling your eyes, but if I don’t say this explicitly someone will claim that you can get a monitor with “better” AdobeRGB color accuracy, a “10-bit” panel, and “HDR support” for $600. What you’re actually getting is a much dimmer LCD with no local dimming, incomplete DCI-P3 coverage, “10-bit processing” (this is 8-bit plus FRC, not true 10-bit color), and a marketing department that decided they could get away with printing HDR on the box even if the display can’t even approximate true HDR performance.

In real-world use, there is absolutely no comparison between a true HDR monitor with a 10-bit panel and a cheaper “HDR” monitor with a regular LED backlight, no DisplayHDR certification, and an 8-bit panel emulating 10-bit color. It makes a real difference that you can immediately see, which is why all true 10-bit displays cost several thousand dollars more.

HDR Experience

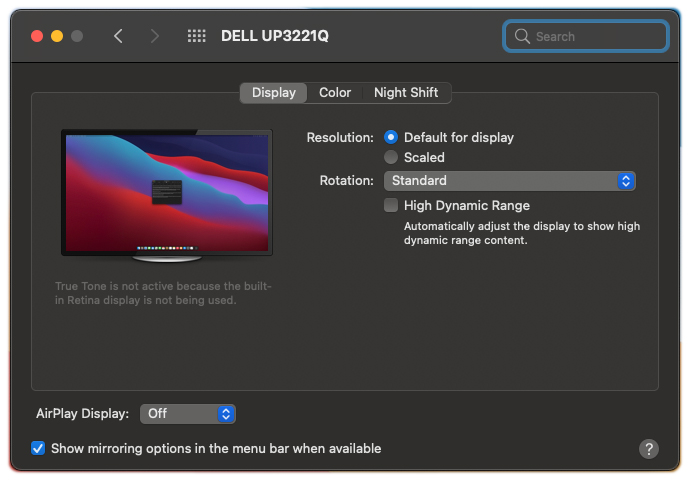

The real revelation when using this monitor, though, came when I turned on HDR on both the monitor and my computer—the Dell supports both HDR10 (ST 2084) and Hybrid Log Gamma (HLG).

The problem is that there is no way for me to show you this performance. Screen recordings, external videos, screenshots… none of them will properly communicate the difference unless you’re actually viewing it on an HDR monitor. Suffice it to say that I spent 45 minutes just switching back and forth, blown away by the color and dynamic range that the display could produce when showing HDR content.

This is nothing like the ugly “HDR Look” that most photographers are familiar with; that’s the result of crushing a wide dynamic range into a limited set of values that a regular display or printer can produce. In this case, the monitor can actually display the full range without compressing anything, revealing more detail on both ends of the histogram, more gradation in the colors from brightest to darkest, and producing an experience that makes it hard to go back.

So, what’s the downside? Well, you need to be producing or consuming content for HDR. SDR content—which includes most of what you’ll be using or looking at on your display day-to-day—looked washed out when viewing it in HDR mode, like a RAW file that hasn’t been processed yet.

I was also disappointed to find that, despite the impressive mini-LED backlight, blooming (also known as the halo effect) is still noticeable in some circumstances. 2,000 individually controlled local dimming zones is a lot—more than any other LCD you’ll find on the market—but a 4K monitor like this has a total of almost 8.3 million pixels, which translates into ~64×64 pixels per mini-LED. If you have a very bright hard-edged object against a black background, it’s simply not enough to create perfectly crisp edges when the edge has to go from a maximum of 1000 nits down to 0.1

The good news is that this only showed up when I used special HDR local dimming test videos that are designed to maximize the issue—it’s not remotely noticeable when watching real-world HDR content since you’re rarely looking at a small white square moving slowly across a perfectly black background. The bad news is that it exists, and you can’t escape it… at least not yet. It’s a limitation of LCD technology that nobody, not even Dell with its record-breaking 2K mini-LED backlight, has managed to overcome completely. Only OLED can turn off pixel-by-pixel, and it suffers from other issues.

Built-In Calibration

The last of the big features included in the Dell UP3221Q is the Calman-powered calibration—a first for a monitor of this size. It’s not Calman validated, it’s Calman powered, promising professional-grade calibration and validation without needing to plug in an external computer or colorimeter.

Normally, I’d criticize a built-in colorimeter as a gimmick for one simple reason: depending on the backlight, many LCDs have issues with brightness uniformity that make built-in colorimeters suspect. Since all built-in colorimeters are embedded into the edge of the display, this means that they calibrate the monitor at the edge, not the center, of the screen. For an edge-lit or un-evenly backlit LCD monitor, this is the kiss of death because it’s really hard to produce uniform brightness, which could throw off your calibration on the part of the screen you actually use.

Of course, the Dell doesn’t have this problem. Since it uses the latest and greatest backlight with more mini-LEDs than anyone else, every 64×64 pixel chunk of screen is individually lit and controlled to an exacting level of precision.

I’m comfortable recommending that you leave your personal colorimeter in its box and rely on the built-in option. However, if you do want to use your own, Dell includes a separate USB port that is used for this exact purpose. If you own a Calman-powered colorimeter, you don’t need an external PC. Just connect the calibration sensor to the dedicated USB port on the bottom of the monitor and use the monitor’s built-in menus to validate or calibrate. Easy peasy.

Miscellaneous Features

Finally, the UP3221Q comes with a few other features that I have to admit I mostly didn’t use.

A monitor hood is included, but I chose to leave it in the box because I don’t get much light in my apartment anyway. The included stand is solid and very flexible, but I chose to attach the monitor to a floating arm instead. Finally, there’s also a feature called Dell Display Manager that lets you “tile” multiple applications onto parts of the screen, but it feels redundant to me. Windows 10 has built-in tiling functionality, and I use an app called Magnet on the Mac to achieve the same thing.

The Dell’s only miscellaneous feature that I actually used is called Picture by Picture: a side-by-side view that allows you to compare two different color spaces while you work. This is useful if you want to see how your image will look in sRGB while editing in a wider gamut color space like DCI-P3 or AdobeRGB. Unfortunately, this feature cannot be used in HDR mode, or to compare HDR against non-HDR, but it’s a handy option since most other “creator” displays only allow you to switch color spaces by changing the output of the entire screen.

Conclusion: Setting the Bar at $5,000

I started this review by asking a question: is there a combination of features that can justify spending $5,000 on a photo editing display?

This seems like a good time to review the pros and cons:

Pros

- 4K resolution

- True 10-bit color

- 2,000 individually controlled local dimming zones

- DisplayHDR 1000 certification for true HDR

- Max brightness of 1000 nits

- Built-in color calibration that actually works

- Thunderbolt 3 connection with 90W power delivery

- Minimal design with thin bezels (except the bottom)

Cons

- Thick and heavy compared to lower-end options and OLED displays

- Plastic casing, not aluminum

- Limited support for external colorimeters (no DataColor support)

- No headphone jack

- No SD card slot

- Blooming/halo effect still noticeable in extreme circumstances

Draw your own conclusions, but in my mind, it’s absolutely worth it.

The price is certainly going to limit the audience here—enthusiasts don’t need true 10-bit color or DisplayHDR 1000 support. But for professionals who do need these things, Dell packed more features into a monitor than anybody else at this price, making it a very tempting option if you’re looking at this level of display for studio use. At least on paper, it keeps up with or out-performs its main competitors from Apple, ASUS, and EIZO for the same or less money, and the 2,000 mini-LED backlight means that its local dimming performance is the best you’ll find among LCDs as of this writing.

Think of it this way: most professional photographers won’t hesitate to spend 5 grand on a high-end lens that, minute-for-minute, will probably see less use than your primarily editing display. We can’t speak to long-term reliability, and there are a few nice-to-have features missing, but if you’re in the market for an elite color-critical editing display and you want the best value for your top dollar, you’ll have a hard time finding a good reason to ignore the excellent Dell UP3221Q.

About the author: DL Cade is an art, science and technology writer, and the former Editor in Chief of PetaPixel. When he’s not writing op-eds or reviewing the latest tech for creatives, you’ll find him working in Vision Sciences at the University of Washington, publishing the weekly Triple Point newsletter, or sharing personal essays on Medium.

Footnotes

1 This is where I really wish I’d had a Pro Display XDR to compare against. In its white paper about the display, Apple explains how they use several specially designed layers of material and microlenses between the backlight and the liquid crystal layer, producing results that should, in theory, far exceed what its 576 individual LEDs would otherwise produce. Unfortunately, I can’t tell you which is better—2,000 mini-LEDs or 576 regular LEDs with Apple’s proprietary technology—because I don’t have a Pro Display XDR to test.↩