If you do any macro or close-up photography, you’ll likely come across the term “magnification.” Even outside of macro photography, most camera lenses include their maximum magnification in the list of specs.

So, what is magnification, and why is it so important in photography? This article covers everything you need to know.

Magnification Definition

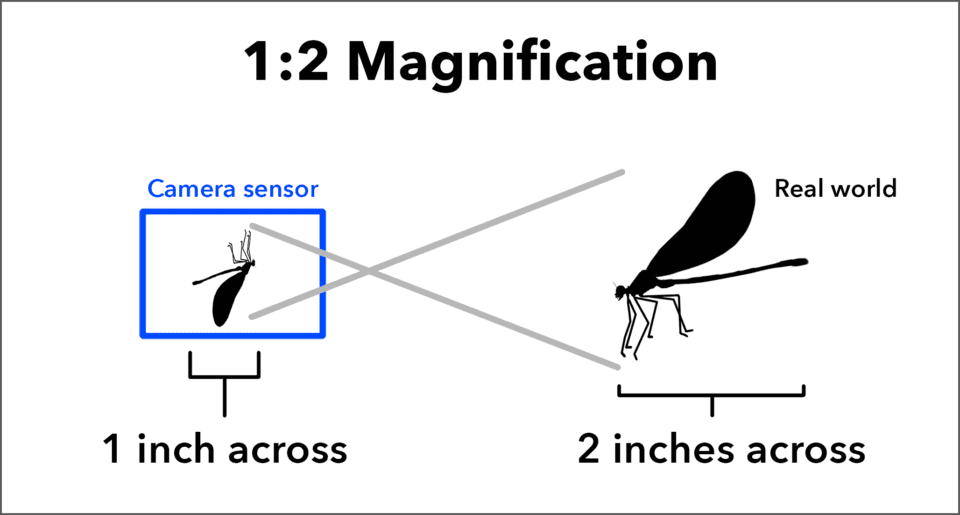

Magnification, also known as reproduction ratio, is a property of a camera lens which describes how closely you’ve focused. Specifically, magnification is the ratio between an object’s size when projected on a camera sensor versus its size in the real world. Magnification is usually written as a ratio, such as 1:2, which is said aloud as “one to two magnification.”

For example, say that you’re doing macro photography, and the object you’re photographing has a projection on your camera sensor which is 1 inch across. If the same object is 2 inches across in the real world, your magnification is 1:2. (It doesn’t matter what units of measurement you use; the important thing is the ratio between the object’s size on your camera sensor compared to its size in the real world.)

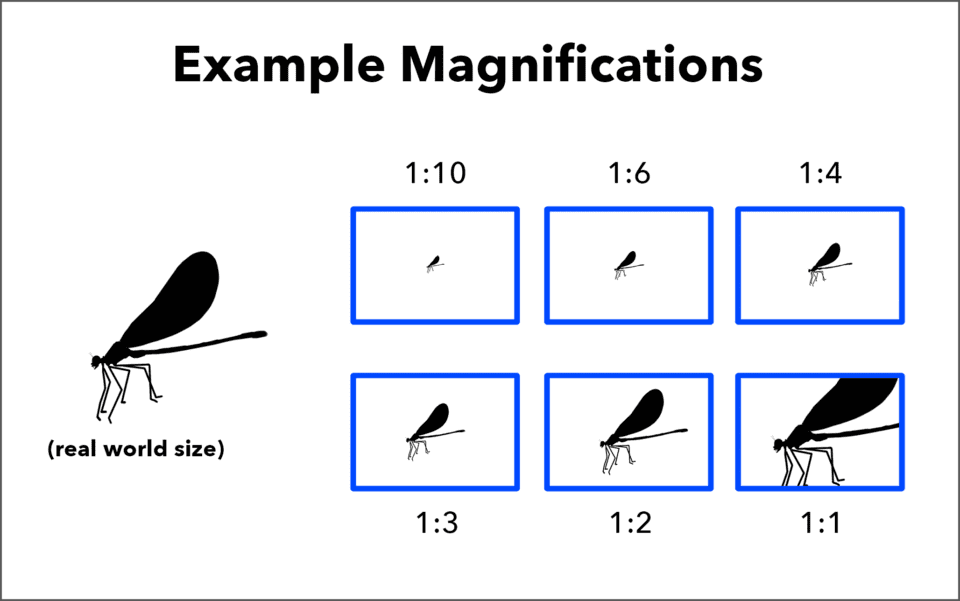

Magnification can also be written in decimal format. For example, 1:2 magnification could be written as 0.5x magnification (which is found simply by doing 1 ÷ 2). This is how magnification generally appears in a list of a lens’s specifications – 0.3x, 0.14x, 0.22x, and so on.

A special case is when the object is the same size in the real world as its projection on your camera sensor. This is 1:1 magnification, also known as 1x or “life size” magnification. It’s important because 1:1 magnification is considered the standard for macro photography, and most macro lenses at their closest focusing distance will be at 1:1 magnification.

The closer you focus, the larger your magnification will be. Macro lenses routinely go to about 1:1 magnification, although some (such as the Zeiss 100mm f/2 Macro) can only go to 1:2 magnification. A few specialty macro lenses can go beyond 1:1 magnification, such as the Laowa 100mm f/2.8, which can go to 2:1. A popular choice among macro photography enthusiasts is the Canon MP-E 65mm f/2.8, which can go all the way to 5:1 magnification! However, this lens can only shoot macro photos and cannot focus on anything distant from the lens; it’s confined to the focusing range from 1:1 to 5:1 magnification.

Most macro lenses tell you their current magnification in the same information window as your focusing distance. For example, on my Nikon 105mm f/2.8 macro, the magnification is visible in the window here:

The Effect of Camera Sensor Size

How does magnification relate to the size of your camera sensor? It’s not as straightforward as you may think.

On one hand, magnification doesn’t change at all because of your sensor size. It doesn’t even matter if you have a sensor; magnification is a property of the lens and the lens alone.

At the same time, you’ll notice that a macro lens can (seemingly) capture a more magnified view of your subject when you’re using a crop sensor camera. What gives?

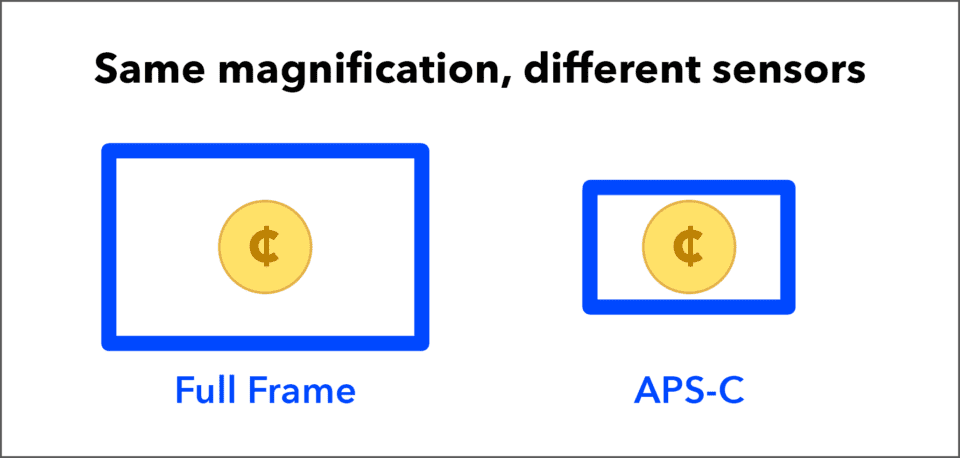

Maybe a diagram will clear things up. Here’s how a sample subject (a coin in this example) looks at the same magnification on two different sensor sizes:

As you can see, the coin’s projection is physically the same size on both sensors. (If it looks larger to you on the aps-c sensor, that’s just an optical illusion; the pixel dimensions are the same.) So, it doesn’t matter what size sensor I put behind the lens – it can’t change the physical size of the projection. The magnification is identical in both cases.

What does change, however, is that the coin takes up a greater percentage of the smaller sensor. If you were to make a print of both of these photos and display them at the same size, obviously the coin would be larger on the photo from the aps-c sensor. So, even though the magnification hasn’t changed, the composition has.

If it helps, you can think about it like this: Shooting with a crop sensor is like cropping an image from a full-frame sensor. In the same way that cropping a photo doesn’t increase magnification, neither does using a crop sensor. But it does make the subject larger in your final image.

The takeaway is that small camera sensors can actually work great for this type of high-magnification macro photography. In fact, if they have smaller pixels than the full frame camera, they’re likely to be at an advantage. (For instance, a 24 megapixel aps-c camera is usually preferable to a 24 megapixel full-frame camera if you need as much detail as possible on a high magnification subject.) It’s similar to the situation with extreme telephoto photography. When your goal is simply to put the maximum number of pixels on a small or distant subject, a crop sensor with a small pixel pitch works very well.

That said, if you’re not at your lens’s maximum magnification (nor very close to it), large camera sensors still have the same benefits as always.

Why Magnification Matters

Unlike some camera settings like shutter speed or aperture, you don’t really need to be thinking constantly about your magnification if you want to get high quality photos. But that doesn’t mean it’s unimportant.

Magnification is important in two main contexts: buying a lens, and figuring out your depth of field.

The first one is straightforward. Now that you understand magnification, you can easily figure out whether a particular lens offers enough close focus capabilities for your needs. For example, you may realize that you need a 1:1 macro lens for what you’re photographing, and a lens that advertises itself as macro but only reaches 1:2 won’t be enough.

Alternatively, some lenses may not advertise themselves as macro lenses, even if they have pretty impressive close focusing capabilities. For example, the humble Nikon 18-55mm AF-P kit lens can reach to about 1:2.6 magnification (0.38x), and the Canon 24-70mm f/4 goes even further to 1:1.4 magnification (0.71x). That’s more than you’d get with many so-called “macro” lenses from other manufacturers! With either of these lenses, you could take close-up photos of larger subjects like flowers, lizards, dragonflies, and so on, without spending hundreds of dollars on a dedicated macro lens.

The Nikon 300mm f/4D lens is famous for its close-up abilities despite not technically being a “macro” lens.

The other context in which magnification matters is in figuring out your depth of field. No matter what lens you have, your depth of field is going to be very shallow at high magnifications, and it falls off dramatically once you’re at 1:1 magnification and greater.

This is because depth of field shrinks as you zoom in and focus closer. Because magnification can be thought of (and even expressed mathematically) as a combination of focal length and focusing distance, there’s no way around it: High magnifications have low depth of field.

If you know what magnification you’re at, you’ll have a good idea of the depth of field you can get. For example, I know that when I’m at 1:1 magnification, I need to use an aperture of at least f/16 in order to get enough depth of field, and maybe even f/22. By focusing a bit farther back – say, 1:2 magnification – it becomes possible to use f/8 or f/11 instead, for the same depth of field.

This is helpful knowledge to have on the fly if you don’t have time to chimp. It’s also nice to know beforehand how to deal with certain magnifications – such as using a flash at 1:1 because of those small apertures, or using focus stacking if you get to extreme magnifications like 4:1 or 5:1 to get back depth of field.

How to Increase Magnification

The only way to increase magnification without resorting to external accessories is to focus closer and closer (or buy a different lens).

If you don’t mind using accessories to go further, here are some things you can do to get more magnification than your lens natively allows:

- Extension tubes/bellows system. Extension tubes are glass-less tubes that go on the back of your camera lens to push it farther from your camera sensor and increase magnification. (Bellows systems do the same thing but are shaped like accordions.) These accessories are very popular for macro photography, and they can extend your magnification significantly. Extension tubes give you the biggest magnification boost if you’re using a wide angle lens. Don’t worry about using a macro lens; even something like an ordinary 35mm prime can get very high magnifications (about 0.5x to 1.2x) when paired with a 20mm or 36mm extension tube. Be sure that whatever extension tubes you get have electronic contacts meant for your camera brand. Otherwise, you’ll have no way of changing aperture with most modern macro lenses.

- Reverse lens technique: I’m not a big fan of this route because it’s much harder to control aperture (aside from some specialty reverse adapters for Canon), but reversing your lens – literally attaching it to your camera backwards – is another potential way to increase magnification. Particularly with a wide-angle or normal lens, this method can offer extremely high reproduction ratios such as 1:1, 3:1, or beyond. The wider your lens’s focal length, the more magnification you could get.

- Dual reverse lens technique: Interestingly, you can also re-use the reverse lens technique by attaching one lens, reversed, onto another’s front filter threads. Divide your lens’s focal length by the reversed lens’s focal length to get your new magnification. You can get extreme macro images this way (such as reversing a 20mm lens on a 100mm lens for 5x magnification). It’s a bit of an unwieldy setup and can introduce unwanted lens aberrations, but it’s fun to experiment with and certainly does work.

- Close-up filter. There are plenty of specialty close-up or macro filters that screw onto the front of your lens. They don’t always have the highest optical quality, so it’s not my top recommendation, but it’s still is a relatively painless way to increase your magnification. In contrast to an extension tube, close-up filters have a greater effect on longer lenses, and comparatively less of an effect on wide-angle and medium lenses.

- Teleconverter. If you have a teleconverter, that’s one of the easiest ways to increase magnification. Specifically, a teleconverter increases your magnification by the same factor that it increases your focal length. For example, a 2x teleconverter will double your magnification – meaning that a 1:1 macro lens will now be able to go to 2:1 or 2x magnification. The biggest issue with this method is cost; teleconverters tend to be more expensive than the other techniques on this list.

The best way to get high magnifications is still to use a macro lens, but hopefully this list gave you some good ideas on how to go beyond that. Personally, my favorite of these methods is to use a set of extension tubes combined with a 35mm or 50mm prime.

I used the Nikon 300mm f/4D in combination with a 1.4x teleconverter to increase my magnification for this photo.

Problems with High Magnification

High magnifications are a lot of fun to use, but it’s not always easy to get sharp photos once you go beyond a certain point. That’s because you’re not just magnifying your subject at these ultra-close focusing distances; you’re also magnifying things like camera shake and subject motion.

On top of that, because high magnifications have such a low depth of field, you’ll also need to be shooting at small aperture settings when you focus especially close. This means you’re in for some photos that are dark and blurry – not to mention out of focus, since focusing is also difficult when your depth of field may be just a few millimeters across!

If your subject is staying still, you can fix most of these issues by focus stacking from a tripod. Even if you don’t focus stack, simply using a tripod allows you to use longer exposures to negate the darkness of f/16 or f/22. It also makes focusing much easier.

However, if your subject is moving, or you’re shooting handheld, focus stacking is much harder, if not impossible. At that point, the best option is to use a flash while practicing your best close-up focusing technique.

These challenges aren’t easy to overcome, but it’s possible to do it with some effort, and that’s half of what makes macro photography so fun! When you do succeed at getting a sharp photo at extremely high magnifications, it’s very rewarding.

Conclusion

Hopefully this article answered your questions about magnification in photography. I’ve also introduced the challenges of getting sharp photos at high magnifications, which you can learn more about in our longer macro photography guide.

If you have any questions about magnification or macro photography, let me know in the comments section below!