One of the more common exposure tips in photography is called the sunny 16 rule. Although it dates back to the early days of photography, and some would argue that it is obsolete at this point, most photographers still hear about this rule while learning about exposure. So, what is the sunny 16 rule, and does it still matter for taking pictures today?

Introducing the Sunny 16 Rule

The sunny 16 rule is a simple way to determine a good exposure for a photograph. On a clear, sunny day, when you are using an aperture of f/16, this rule recommends a shutter speed equal to the reciprocal of your ISO (1/ISO value).

At ISO 100, for example, use a shutter speed of 1/100th of a second. At ISO 200, use a shutter speed of 1/200 second. That’s all there is to it.

Keep in mind that all the various exposure settings recommended by the sunny 16 rule are not equally worthwhile, even on a sunny day, and the rule itself doesn’t claim they are. For example, you probably will not want to shoot at settings like f/16, ISO 3200, and 1/3200 second for many photos.

Instead, the sunny 16 rule is all about providing a quick set of exposure settings which will result in a photo of the proper brightness. You still need to pick from those settings to determine which one is ideal for the scene you’re capturing.

Also, it is easy to expand the sunny 16 rule further by assuming a different aperture value or a darker scene. For example, if the settings f/16, 1/100 second, and ISO 100 provide a bright enough photo on a sunny day, the same will be true for f/11, 1/200 second, and ISO 100 in the same conditions. That still counts as a “sunny 16 exposure,” even though you’re at f/11. These numbers are meant to be shifted.

Does the Sunny 16 Rule Work?

Although the sunny 16 rule can work as a general guideline, you will find situations – even on clear, sunny days – in which it leads to underexposure or overexposure. The colors and reflectiveness of your subject make a big difference here, and so does the direction you face (into the sun, or away from it). If your standards are too high, the sunny 16 rule plainly does not work.

However, it never was meant to be a precise way to find your optimal exposure – simply a guideline to help you down the right path. By following the sunny 16 rule, you immediately know a range of camera settings that will be roughly correct, and you have the ability to bracket or consult your meter to refine things more precisely.

What About Your Camera’s Meter?

Most photographers don’t use the sunny 16 rule for their daily work. Instead, they use the camera’s own meter to find a good exposure, adjusting exposure compensation as needed. That’s probably what you should do as well.

The sunny 16 rule isn’t better than your meter in most cases. Originally, it was used as a way to calculate exposure if you didn’t have a meter with you, or to serve as a sanity check on your meter’s reading (since you couldn’t just review a photo you had taken with film).

Today, essentially every digital camera on the market has a built-in meter, and you can review your photos immediately to judge exposure (as well as consult tools like your histogram for greater precision). So, the sunny 16 rule is a bit of a relic. It is rarely used in the field any longer.

However, that does not mean this rule is useless. Personally, I believe that you can improve your photography skills by forming a deep, intuitive understanding whenever you learn about an important topic like exposure. In this case, the sunny 16 rule helps you learn an instinctive range of reasonable settings for a scene even before you decide to take a photo.

In other words, the sunny 16 rule is a good starting point to formulate your own “mental meter” if you have not begun to do so already. It is also a useful way to teach beginning photographers about the concept of exposure – how your camera settings relate to one another, and to the scene you are photographing.

Sunny 16 Rule Chart

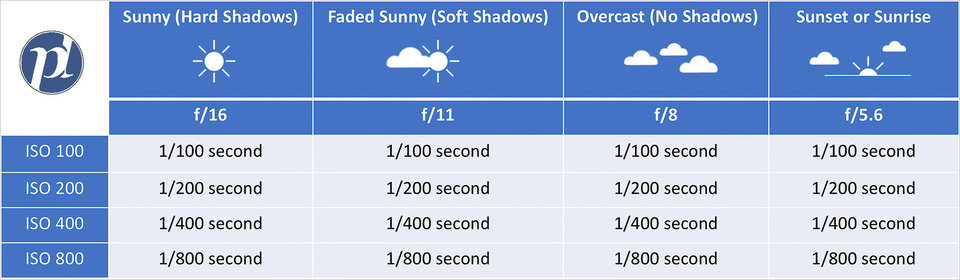

Below, you will find a chart with the sunny 16 rule’s recommended exposure settings. This chart also includes the equivalent exposures for darker scenes:

Note that these values are not precise, and, again, the optimal exposure depends upon a number of additional factors. It is important to check your camera’s meter reading if you want a more specific suggestion for exposure. Also, the chart above does not cover all the potential settings which will work for a given scene. (You certainly can take high-quality photos at sunset at f/11, for example.)

Conclusion

The sunny 16 rule is not the optimal way to capture a good exposure. It is not even a technique, most likely, that you will need to think about at all in the field. Useful tools like your camera’s built-in meter, histogram, and blinkies have rendered basic tricks like this generally obsolete in today’s world.

However, for photographers who are trying to expand their personal skillset and intuitive understanding of photography, the sunny 16 rule still has value. There is something to be said for refining tools like your “mental meter” and visualization skills if you want to become a better photographer. It also helps beginners understand the relationship between a scene’s appearance and the camera settings needed to capture it successfully.

So, there are at least a couple good reasons why the sunny 16 rule has lasted until today (aside from old habits dying hard). Hopefully, this article helped you determine whether or not it will be useful for your photography as well.