One of the most misunderstood parts about landscape photography is the correct way to fit your entire scene within a photo’s depth of field. Where do you focus? What aperture should you use? You might think that these questions are easy to answer with a hyperfocal distance chart, where you provide your focal length and aperture, and the chart tells you exactly where to focus. There’s only one hiccup — if you want the sharpest possible results, these charts are spectacularly wrong. For most landscape and architectural photographers, that’s a big deal. This article explains everything about hyperfocal distance charts: what they are, why they fail, and where to focus instead.

1) What Is Hyperfocal Distance?

The technical definition of hyperfocal distance is quite simple: It’s the closest point to your camera that you can focus, while still ending up with an acceptably sharp region at infinity (i.e., your background in most photos).

Why did I put “acceptably sharp” in bold? Because it’s way too ambiguous. I’ll go more into that later, but this is the main reason why hyperfocal distance charts aren’t workable — and didn’t even work in the past, regardless of photographers’ changing standards for sharpness over time.

2) What Are Hyperfocal Distance Charts?

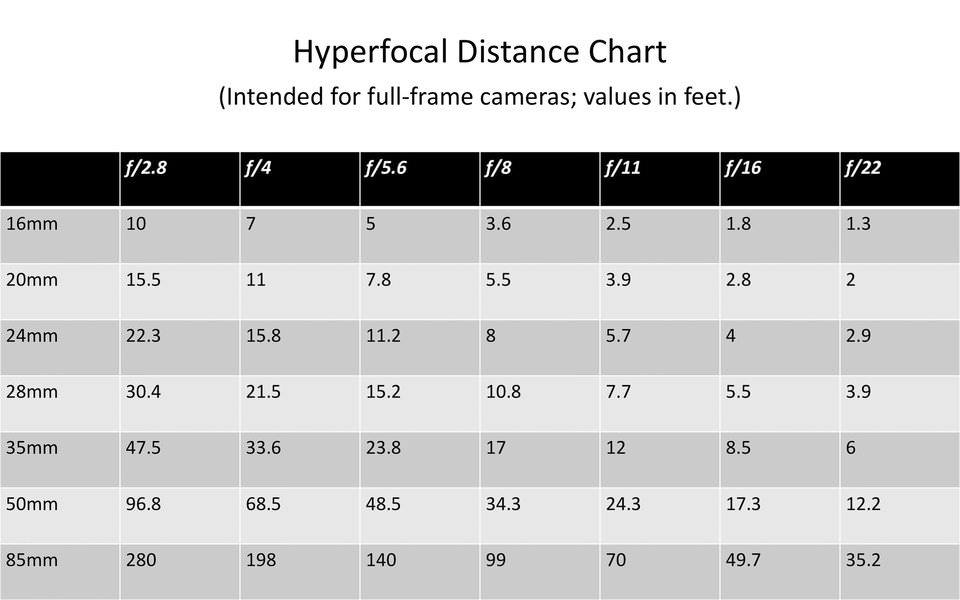

Typical hyperfocal distance charts look like this, although there are different ones for every sensor size:

Essentially, you input your aperture and focal length, and they output the closest point you can focus and still capture an acceptably sharp background. It’s not just charts, either; you’ll also find hyperfocal distance calculators and apps that give you the exact same values, but with some more flexibility on the inputs they allow.

But, since they aren’t accurate anyway, you don’t need to worry about any of this.

3) Why Are Hyperfocal Distance Charts Inaccurate?

Hyperfocal distance charts are wrong because their definition of “acceptably sharp” is sloppy and inflexible.

When the first hyperfocal distance charts were designed, someone decided that an acceptably sharp background contained some blur — enough to notice in a medium-sized print — but, all things considered, not a massive amount. After that point, nearly every other hyperfocal chart followed suit.

To be more specific, most hyperfocal distance charts are calculated to give you exactly 0.03 millimeters of background blur. (That’s the physical size of the blur projected onto your camera sensor.) If you’ve ever heard the term circle of confusion, this is all it’s talking about: the size that an out-of-focus pinpoint of light appears on your camera sensor itself.

So, what’s wrong with this definition? Perhaps your first thought is that this particular value, a 0.03-millimeter circle of confusion, happens to be too large for today’s world of high-resolution cameras, large prints, and 4K monitors. If we simply created hyperfocal distance charts with a more demanding value — maybe 0.015 millimeters, or 0.01 millimeters of blur — we’d be fine. Right?

Nope. Not at all.

That’s because the biggest issue with hyperfocal distance charts isn’t that their circle of confusion is too large. Yes, that is a problem, but there’s an even more important one: These charts recommend the exact same focusing distance for a given aperture and focal length, and it doesn’t change, no matter the landscape.

Say that you’re shooting with a 24mm lens, and you want to use an aperture of f/8 (since it’s the sharpest one on your lens). Logically, your focusing point should change depending upon the scene in front of you — whether there’s a foreground element nearby, or whether you’re at an overlook with everything in the distance. But, according to a hyperfocal distance chart, all you need to do here is focus eight feet away from the camera, and you’re set.

That is very, very inaccurate. Instead, the best method is to change your point of focus depending upon the scene. So, if every element of your image is in the distance, focus at the horizon. Or, if there’s a foreground element nearby, focus closer than eight feet (and use a smaller aperture while you’re at it).

If every one of your photos has an “acceptably sharp” background, that’s all it will have. It won’t have the best possible sharpness. It won’t keep your foreground as sharp as possible. All that it guarantees — and all that a hyperfocal distance chart tells you — is that your background will have exactly 0.03 millimeters of blur for every single photo.

So, drat. It seems like hyperfocal distance is a useless topic that won’t help you take sharper photos at all. Right?

Not necessarily. On one hand, it is true that hyperfocal distance charts aren’t useful; that should be fairly obvious by now. But that doesn’t mean hyperfocal distance in general is a bad concept. In fact, there is still a fantastic way to find the right focusing distance in landscape photography. It is also, I might add, quite a bit easier than pulling out a chart each time you take a photo.

Hyperfocal distance is still useful in situations like this, since I have to find the perfect place to focus in order to capture these flowers and mountains sharp simultaneously.

4) The Optimal Focusing Method

Before going into the proper way to find your focusing distance, let’s examine the definition of hyperfocal distance one more time:

It’s the closest point to your camera that you can focus, while still ending up with an acceptably sharp background.

The holdup so far is that “acceptably sharp” has nothing to do with the scene you’re photographing. Is there a way to change that?

Indeed there is. Instead of defining it as an arbitrary, inflexible circle of confusion — no matter how large or small — I propose that an acceptably sharp background is one that is equally as sharp as the foreground. In other words, the background circle of confusion should be exactly the same as the foreground circle of confusion.

That, and that alone, will give you the sharpest possible results across the entire frame. You no longer have to worry about your foreground being vastly less sharp than the background; just focus closer until the two are equally sharp. And, if your “foreground” (the closest element in your photo) is a distant mountain, all you need to do is focus at infinity, and you’ll achieve a blur much smaller than 0.03 millimeters.

The closest element in this photo is quite far away from my camera. Functionally, it’s at infinity. So, why would I focus 8 feet away (which is what the hyperfocal distance chart recommends for a 24mm photo at f/8) rather than just focusing at infinity? Something isn’t right.

I can see some arguments from people who prefer, in a particular landscape, that either their foreground or background is significantly sharper than the other. That’s fair — but this technique is about maximizing your sharpness from front to back. If that’s your goal, as is the case for most landscape photographers, you’ll want the two to have matching levels of sharpness.

There is only one question left: How do you actually find the point that results in equal foreground and background blur? Is it all just guesswork?

Actually, the optimal method is remarkably simple: Find the closest element in your photo. Estimate how far away it is. Double that distance, and focus there. (That’s the real hyperfocal distance, as defined by equal foreground and background sharpness.)

If the closest element in your photo is one meter away, the hyperfocal distance is two meters away. If the closest element in your photo is ten feet away, the hyperfocal distance is twenty feet away.

This is called the double-the-distance method, and it’s something that should be stuck in the head of almost every landscape photographer. Focus twice as far as your closest object. Done.

In this image, the nearest rocks are roughly four feet away from the plane of my camera sensor. So, to capture the sharpest possible result in both the foreground and background, I just doubled the distance and focused at eight feet.

If you’re worried about estimating distances perfectly, don’t be too concerned. First, this is no different from what you’d do with a normal hyperfocal distance chart — trying to focus at exactly fifteen feet, for example — so it isn’t anything new. And, on top of that, you don’t have to be totally accurate. If you focus at 2.8 meters rather than 3 meters, your photo will still be vastly sharper than if you followed a “proper” hyperfocal distance chart in the first place.

Another great thing about the double-the-distance method is that it doesn’t depend upon your focal length or aperture at all. The proper spot to focus in every single landscape, no matter your settings, is double the distance (again, assuming that you want maximum foreground-background sharpness).

The settings you use are still quite important, of course. If your landscape extends from three feet to infinity, and you’re focused at six feet, you wouldn’t want to use an aperture of f/2. But even if you do use an aperture of f/2, you’ll still maximize the sharpness in the scene; it’s just better to use a more typical landscape aperture of f/11 or so instead.

Actually, that’s another important point. Now that you’ve found the best possible spot to focus, what aperture should you use for the sharpest photo? A smaller aperture will provide as much depth of field as possible, but it also decreases your photo’s sharpness due to diffraction.

That’s also a crucial technique to learn — and, once again, there is an optimal answer — but it is too long to describe in this article. I’ve already covered everything in detail in my article on choosing the sharpest aperture. That’s a great place to start.

So, is that it? You simply focus at double the distance for every photo, and you’re set?

Yes indeed. For landscape photography, this method is a fantastic tool to have in your kit. It’s how I focus for every single landscape I encounter, given that I want the maximum possible depth of field. Don’t worry yourself with hyperfocal distance charts, because their definition of “acceptably sharp” isn’t up to par. Instead, focus twice as far as your closest subject, and you’ll be set.

5) Are Lens Aperture Scales Also Inaccurate?

Some lenses (though fewer nowadays) have built-in scales to tell you how much depth of field you’ll get at a given aperture. They look something like this:

People frequently ask me whether it’s possible to use these depth of field scales to focus properly and use the optimal aperture. Or, like hyperfocal distance charts, are these scales also wrong?

In practice, there are a couple reasons why you’d want to avoid using these lens scales as a guide for the best possible place to focus. First, you have to ensure that the distance markers on your particular lens are accurate in the first place. Not all of them will be calibrated perfectly, and it’s very possible that your lens will misidentify how far away it’s focused. For example, it may say that it’s focused at five feet, but it’s actually focused at seven or eight feet instead.

More than that, though, these focusing scales are also calibrated with a 0.03 millimeter circle of confusion in mind. This means that their depth of field markers are — to say the least — quite generous. I mentioned earlier that 0.03 millimeters of blur is fairly noticeable on medium-sized prints, and that’s still true. If you follow the indicators on lenses like this, your horizon and foreground will each have 0.03 millimeters of blur. That’s not a massive or unforgivable amount, but, very often, you can do better.

So, as a whole, I wouldn’t use these scales to focus properly in a landscape. They’re not quite as bad as hyperfocal distance charts, but the optimal method is, like always, double-the-distance.

Here, the closest objects in my frame are some grasses at the bottom of the image. They were only about a foot away from the plane of my camera sensor. So, I focused two feet away and used a very small aperture of f/16.

6) Conclusion

Hyperfocal distance charts are wrong for two reasons. First, their definition of an “acceptably sharp” background has a 0.03-millimeter circle of confusion, which isn’t particularly sharp. And, even worse, these charts don’t change at all depending upon the landscape in front of you. So, they simply aren’t flexible.

Instead, it’s best to define an “acceptably sharp background” as being “equally sharp as the foreground.” That maximizes definition across the entire frame, from top to bottom, and it lets you do away with the issues of traditional hyperfocal distance charts.

Best of all, finding this point — the correct hyperfocal distance — is simple. You have to locate the closest object in your frame, estimate its distance from your camera sensor’s plane, and then double that distance.

For landscape photographers, this information is essential. If you’ve ever been at a scene with a great foreground and background, but you’ve been unable to capture both as sharp as possible at once, this is the proper hyperfocal distance. Forget charts and calculators; forget depth of field scales on your lenses. By focusing at double the distance, you can maximize the sharpness of a scene without compromise, and it is far easier to put into practice, too.

Here, the nearest object in my photo is the grass at the bottom of the image. It’s about five feet away. So, I focused ten feet away, which lines up roughly with the front of the island in the middle of this stream.

If you have questions about hyperfocal distance charts, depth of field, doubling the distance, or anything else I covered, feel free to ask about it below. This is a higher-level topic, but it’s an important one that every landscape photographer should know. There’s certainly enough misinformation floating around online about hyperfocal distance, so I’ll do my best to address any concerns in the comments section.